I first saw Luchita Hurtado’s work in LA a few years ago when a tiny alternative gallery owner was desperately trying to keep control of her archive. Hauser and Wirth swooped in and now there is an exquisite show at the Serpentine Sackler (what will they do about this appellation?) in London, in an early Zaha Hadid building. The exhibition cements recognition for Hurtado’s expressive and unique vision. Her husband Lee Mullican was the more recognized figure as was often the case with married artists of the time. All that has changed. This work painted just recently: she’s 98.

Kathy Acker at the ICA London

Where was I when Kathy Acker was appropriating text and imagery from Rimbaud and performing at the Kitchen and tattooing her body and raging against sexual conformity? Working at MoMA and Lincoln Center and getting married and having babies. I felt utterly conventional and bougie at this exhibition at the ICA London and yet at the time the artists and filmmakers surrounding me seemed avant-garde. Acker’s art needs to be read carefully as well as seen, and so I have catching up to do.

Mary Quant at the V and A London

The Mary Quant exhibition at the V and A shows off a holistic designer whose ideas about everything from fabric content to how make up should be packaged to the needs of modern young women was part and parcel of what she thought her role as a change agent was. A striking difference from how Christian Dior thought how women should be packaged in an adjacent exhibition. What a difference a decade made.

Michelangelo stays at the Met

For the few years I worked at the Services Culturels housed in the former Payne Whitney mansion across from the Metropolitan Museum on Fifth, we used this rather nondescript statue as a coat or hat rack, ashtray, or place to wad a used cocktail napkin. When it was discovered to be a vrai Michelange I was rather nonplussed. My office which was vaguely like a bordello with a white shag rug and dark walls in a remade attic space was only one of many odd nooks in the building which Miss Helen Whitney had done up when upper Fifth was the boonies. Still the statue conferred a sense of decorum and history during a time of my life dearly lacking in same.

Ratmansky Trio at ABT shows off his Russian roots

In between their sumptuous productions of Whipped Cream and Swan Lake, ABT programmed a trio of of Alexei Ratmansky works that felt oddly like a night at their next door neighbors at NYCB.

Ratmansky is probably the most complete choreographer working today. What do I mean by that? As heir to the full panapoly of Russian traditions, and as keeper and burnisher of that flame, many of his ballets—even the more contemporary ones-- still have a Russian feeling and elements that remind of Nijinsky’s Faun or Russian folk traditions. Yet he has learned from Robbins and Balanchine as much as anyone.

Songs of Bukovina from 2017 appears at first to draw on Jerome Robbins’ Dances at a Gathering more than anything else. But then you notice the flat-footed chorus with its flexed feet or the folkloric jumps and poses and the hybrid nature of his work comes to the fore. Isabella Boylston, a Sun Valley, Idaho native manages to imbue the piece with a Russian-inflected insouciance that is lovely and carefree.

On the Dnieper falls more directly in the tradition of ABT story ballet, it received its world premiere in 1932 at the Paris Opera ballet and is 100% in the Russia camp. A story of a tragic Ukrainian love triangle, the period costumes and full-on acting by the cast has an almost kitsch quality that as someone who was emphatically reared on Balanchine finds studied. Still Christine Shevchenko—who is Ukranian-- is such a divine dancer that all else falls away when she takes the stage especially after she becomes the tortured bride.

The Seasons, Ratmansky’s newest work for the company which premiered this week is another of his deep dives into Petipa and as such feels entirely period with added hallmarks of early Balanchine who also drew from this well. It is a joyously danced work which Ratmansky created as a thank you to ABT. (see above video) With moments of choreographic fun and frolic, its four part structure lends itself to lots of chorus, holding poses, and gaiety. I saw the second cast led by Summer’s Stella Abrera (Isabella Boylston danced the first night) Herman Cornejo was alas injured and so Blaine Hoven who had danced in Bukovina was pressed into service and Calvin Royal took Hoven’s spot in the Autumn section.

The house was not full and I imagine that ABT stalwarts find an evening like this one which does not deliver the full on Sleeping Beauty experience a little more challenging. I remember Ratmansky telling me a couple of years ago at the Rolex Arts and Culture weekend, that he’d had no real mentors in Russia, that, “everything my teacher taught me was nonsense.” Yet, as these three ballets show, he is heir to some of their tradition nonetheless.

Scene from The Seasons. Photo: Rosalie O’Connor.

The Souvenir, a tragic story of passionate, blinding first love from Joanna Hogg

I join the chorus of amateurs of The Souvenir, Joanna Hoggs auto-movie--with Tilda Swinton looking like the Queen and her daughter Honor—an unusually fresh faced ingenue—about the first love relationship of a young woman and her elegant junkie boyfriend. The film, purportedly a thinly disguised memoir of Hogg's relationship with an older, brilliant man who seduces her through Fragonard along with the sex she clearly adores, really takes off when a friend of his asks Julie at dinner, "how does it work?"—meaning, how does an innocent like you get it on with a heroin addict?? Of course until then, besides taking the track marks on his arm for a wound that won't heal, Julie is ignorant of his addictive proclivities, as are we (unless we study the spoiler reviews), and even then it's a shock. The film ends up being a torture to watch as she repeatedly supports his habit and dissolute lifestyle. I wanted to knock her upside the head. But, I also was jealous. To be so blindly in love is something achievable only very early in one's life.

Jadwiga Grabowska-Hawrylak, a Polish architect revitalized a city left in ruins

The very complete Patchwork show of the architecture of Polish woman Jadwiga Grabowska-Hawrylak ended last week. In the early seventies my husband joined a posse of American planners and architects who went to Poland on Marshall Plan money to help revitalize the country. They found a bleak environment and harsh post war conditions. Grabowska-Hawrylak was associated with Wroclaw (formerly Breslau) as a student and as a prime mover of the reconstruction of the city along with a similar, domestic cell of architects and planners. At the Center for Architecture, a panorama of her built and unbuilt works told a tale of public housing, education, cinema, conservation, capitalism and socialism and a country left in ruins. Social Realism gave way to urgent needs of housing the population irrespective of theory. Prefabs were required. Residents jokingly called their housing estates The Principality of Monaco or Manhattan. A model of her Grunwaldzki Square project had been built out of Styrofoam and it was magnificent.

Photo: ,Courtesy The Center for Architecture, by Chris Niedentha

Afternoon of a Faun: James Lasdun writes MeToo as a Thriller

Spurred on by a review by Katy Waldman, I read James Lasdun’s slender but riveting novel Afternoon of a Faun. It was probably the frisson of the title drawing me in at first (Jerome Robbins ballet drawn from the same source is a particular favorite) but Lasdun has managed the hat trick of both taking a story ripped from the headlines and crafting a thriller around it. An unreliable protagonist, an unreliable narrator and an unreliable subject and #MeToo combine for some page-turning narrative delights and I could not put this down. It felt so good to be engaged in a novel, I am finding it a challenge to lose myself in fiction these days as it cuts so close to the bone. Highly recommended.

Bjork's Cornucopia at The Shed: a Phantasmagoria of Utopia

So many connections passed through my mind last night as I watched the premiere of Bjork’s Cornucopia, an original production conceived for The Shed.

It was my first visit to The Shed and I was only able to peek into a couple of the other spaces, so I cannot really comment on them other than to say the space is huge and it has the misfortune to be adjacent to the Hudson Yards garish neon commercial signs and the hulking Heatherwick stairway to nowhere. The whole thing, the hall, the production, the staffing is certainly a massively expensive undertaking and one cannot help but think of all the theaters in NY in dire need of funding.

But once inside the McCourt theater I understood that The Shed was an excellent space for accommodating the visions of people who think BIG. (As an Angeleno I held myself in check from allowing any reflux from the disastrous McCourt stewardship of the Dodgers to affect my reactions. It’s not only arms manufacturer and oil company trustees who should be held to account.)

Architect Liz Diller, who slipped into the performance just after it had begun, and Bjork and her creative team think big and I admire that. We don’t have enough women thinking big in this very fearless way. The McCourt has every production bell and whistle imaginable, and they were used in full measure for Bjork’s grand vision of Utopia.

I confess I hadn’t been to a pop concert in a long time, and I imagine that digital visual is also being used by other performers. But there could be no more immersive production than this one. The Met Opera in New York and Artistic Director Alex Poot’s former digs at the Park Avenue Armory and Madison Square Garden are the only spaces I can think of in New York that could accommodate this kind of production grandeur.

Bjork has imagined a world where children have a true voice. The appearance at the outset of The Hamrahlio childrens choir in front of the stage set that tone immediately. In their Icelandic costumes they welcomed the sold out audience with runes and sopranos that warmed up the vast hall considerably. In fact Iceland is evoked in many ways throughout the performance.

Bjork’s back up performers on stage are a troupe of Midsummer Night’s Dream-ian fairy sprites (all with the Iceland surnames of ---dottir) who can play a mean flute, even if the instruments have been molded into a circle which surrounds Bjork for four to play at one time, and they dance, cavort and lead us into Bjork’s unique world.

Bjork’s other collaborators--all overseen by director Lucrecia Martel--a production designer, Chiara Stephenson who did the magic mushroom-like platforms, a veteran drummer Manu Delago who roves to many stations and alt-percussive instruments (a watery tank a particular favorite of mine), a media artist Tobias Gremmier whose digital projections on a beaded curtain (Four Seasons restaurant anyone?) and a rear wall were a combination of Georgia O’Keefe and Karl Blossfeldt floral stamens and pistils, costume designers Iris Van Herpen who outfitted Bjork first in white puffed balls and a black ruff (very eighties, it reminded me of my wedding dress which was made with the BIG puffy sleeves then in style) and then Olivier Rousteing’s gossamer feathered birdlike contraption, and James Merry who did the many headpieces which were very Klingon-like and mostly obscured Bjork’s face, all combined in this fantasia which begins and ends with Bjork’s vision for our planet.

She’s worried. A dire message about global warming appears on the curtain. The young Swedish girl who began the global school walk-out movement is also given curtain time to make her case that adults are now behaving like selfish, spoiled children intent on wrecking our precious resources.

The production has an Alice in Wonderland-slipping-down-the-rabbit-hole feel but as someone who is not entirely familiar with the Bjork canon, I can only say that sometimes I wished for more Bjork and less production. When she steps out in front of the curtain onto a small platform and into the audience there is a certain raw, unadorned quality that is very meaningful.

Nevertheless, her heart is all over this outsize confection which runs the full month (I hear it is sold out) and her originality and dedication to her work is apparent in everything she sings and every move she makes. Under the Big Top of The Shed, she still manages to emerge as a truly original visionary. I look forward to catching up with the other project spaces soon.

Photos: Santiago Felipe, 2019. Courtesy One Little Indian/The Shed

An homage to Picasso's Women and biographer John Richardson at Gagosian

Pablo Picasso, Buste de femme (Dora Maar), 1940, Oil on canvas, 29 1/8 x 23 5/8 in, 74 x 60 cm, © 2019 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York, Photo: Erich Koyama, Courtesy Gagosian

When I corresponded with Dora Maar to try to pin her down for an interview for our WNET Picasso documentary at the time of last major Picasso retrospective at MoMA, she was slippery but made sure to ask after John Richardson's whereabouts as she wanted to reconnect with him. She was a tough get, but he got her.

A newly opened homage to Richardson, Picasso's biographer, is also a testament to Gagosian's ability to pull together so many important images in record time. Some of the images of Marie Therese appeared in the Tate Modern retrospective last year. But others felt new to me. Perhaps it’s because I see these images in a slightly different way each time. Recently I too have been examining the role of the women in Picasso’s life and work.

To that end, I often revisit Richardson/Picasso and I'm always impressed by the wealth of personal detail and the profound sense of humor that he brought to this artist, the most chameleon-like of subjects. Richardson organized a number of electric Picasso shows at Gagosian and though this is a less ‘curated’ affair, it still invokes the complex relationships he had with so many of his lovers/muses/wife.

The last upcoming volume of his Picasso biography which will be published posthumously will surely add more delicious tidbits as well as enormous scholarship and I eagerly await it.

CAMP: Notes on Fashion arrives flush with gaiety at the Met Museum

Camp is Here! You might be watching the red carpet stars but the exhibit itself is where the buzz is, and this year is no exception.

Coming on the heels of Heavenly Bodies, an exhibition of religious and religious-inspired fashion that was so rich it migrated on bended knee up to the Cloisters, Camp skews in the exact opposite direction—with delightful results, if not at quite the same level of wow. From the sublime to the ridiculous to borrow a phrase I believe curator Andrew Bolton and his team at the Met Museum Fashion Institute would roundly endorse.

Bolton has been asked what is camp. Well, it appears to be just about everything under the sun if you say it is. Bolton says Camp is most emphatically aroused when society is divided, eg before the French Revolution, the sixties, the eighties, and of course, today.

Section A, Bolton’s “Whispering” galleries kitted out in ballet pink posit that Camp began in the court of Louis Quatorze, the Sun King. Moliere, his court playwright, coined the verb ‘se camper’ or to ‘posture’, (similar to ‘flaner’ which connotes a more active sashaying down the street; Vogueing a contemporary take) “Camp about on one leg. Put your hand on your hip. Wear a furious look. Strut about like a drama king” his character Scapin advises. The mannequins have fascinators, pink bows, glittery pink caps by Stephen Jones. They look innocent but they are often wicked! Judy Garland croons Over the Rainbow.

Homework Assignment #1:

Binge watch Versailles (Amazon) and the film A Little Chaos (Netflix) before you come as you will have the full flavor of the early period of Camp.

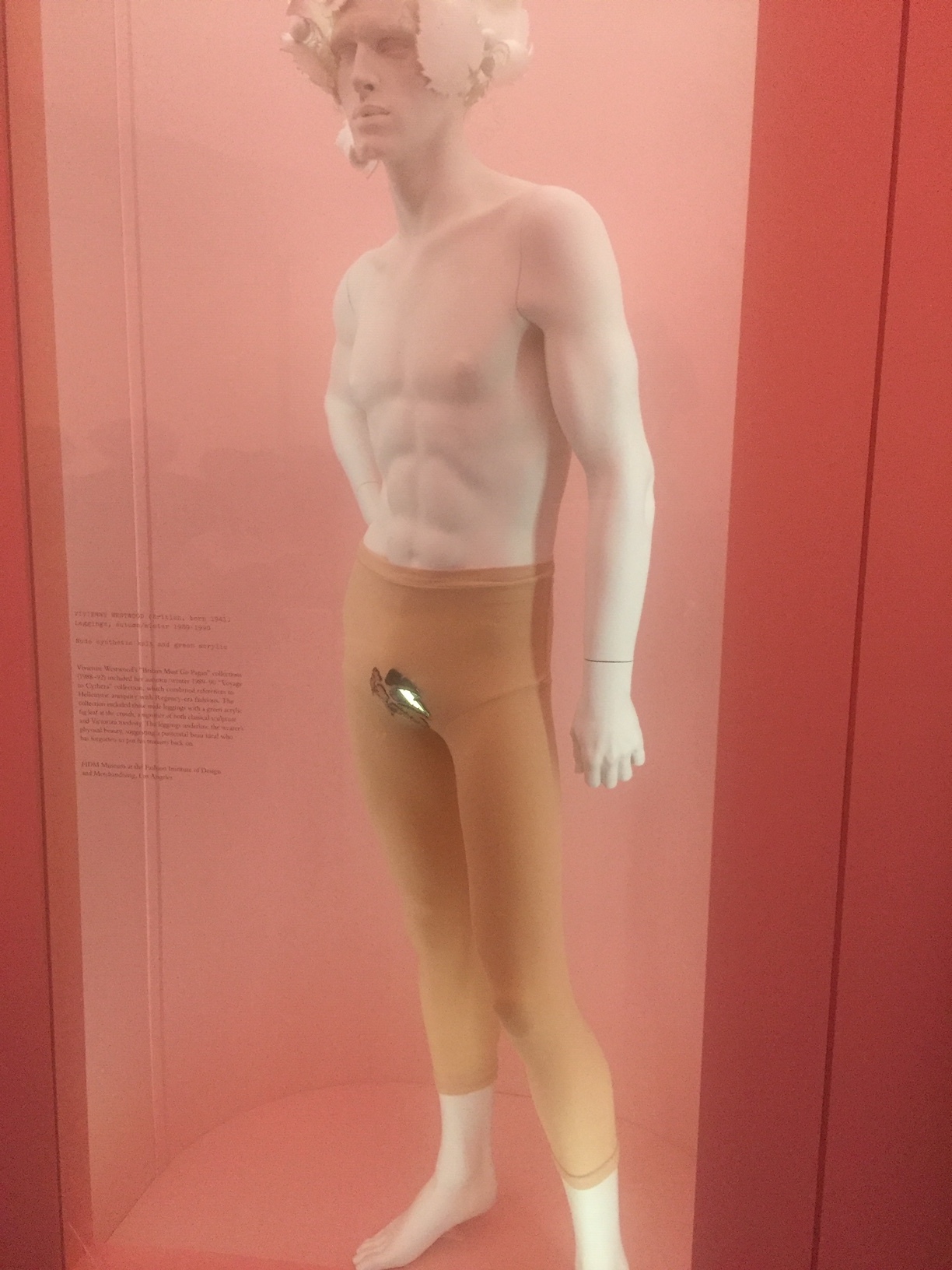

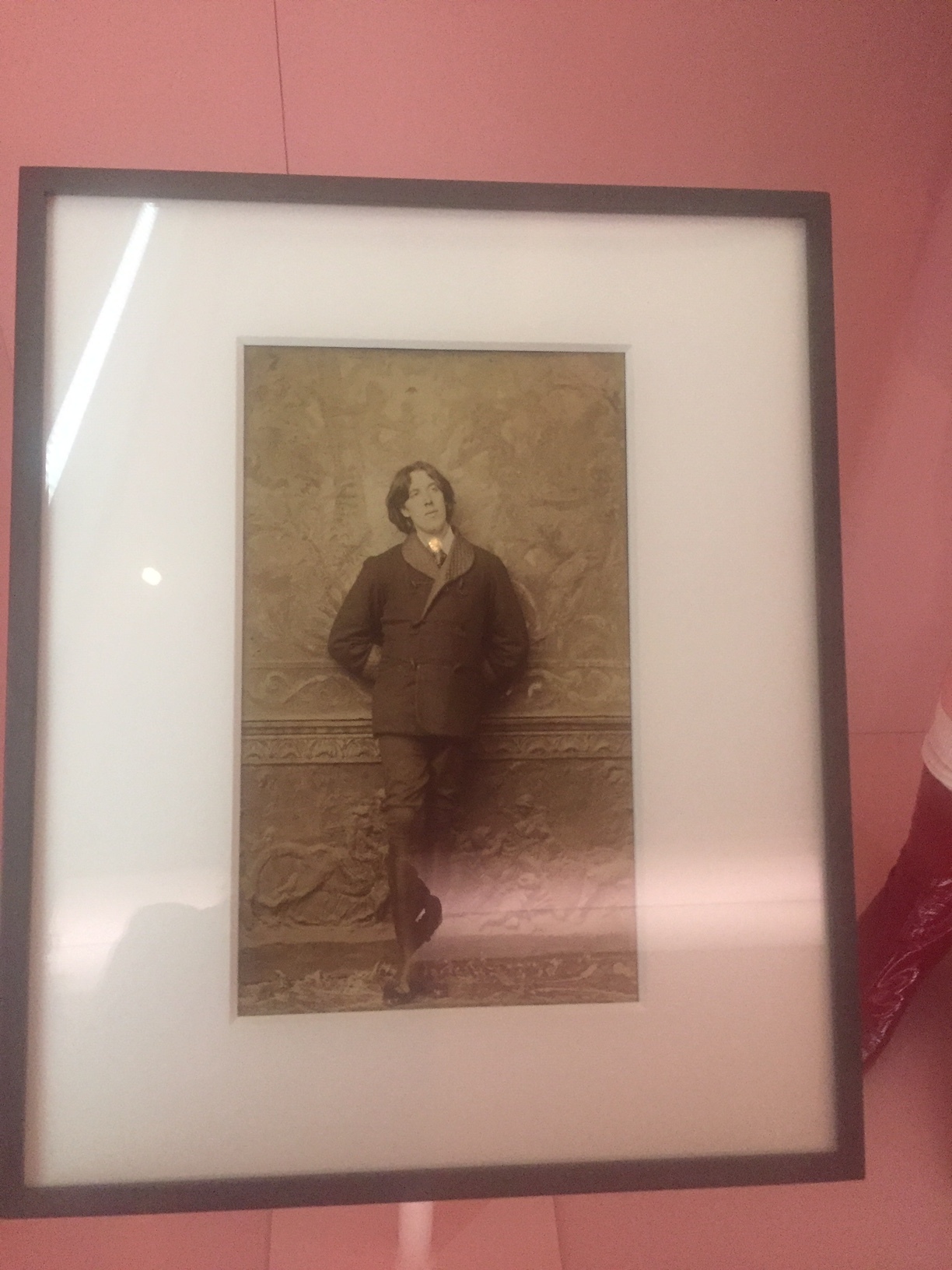

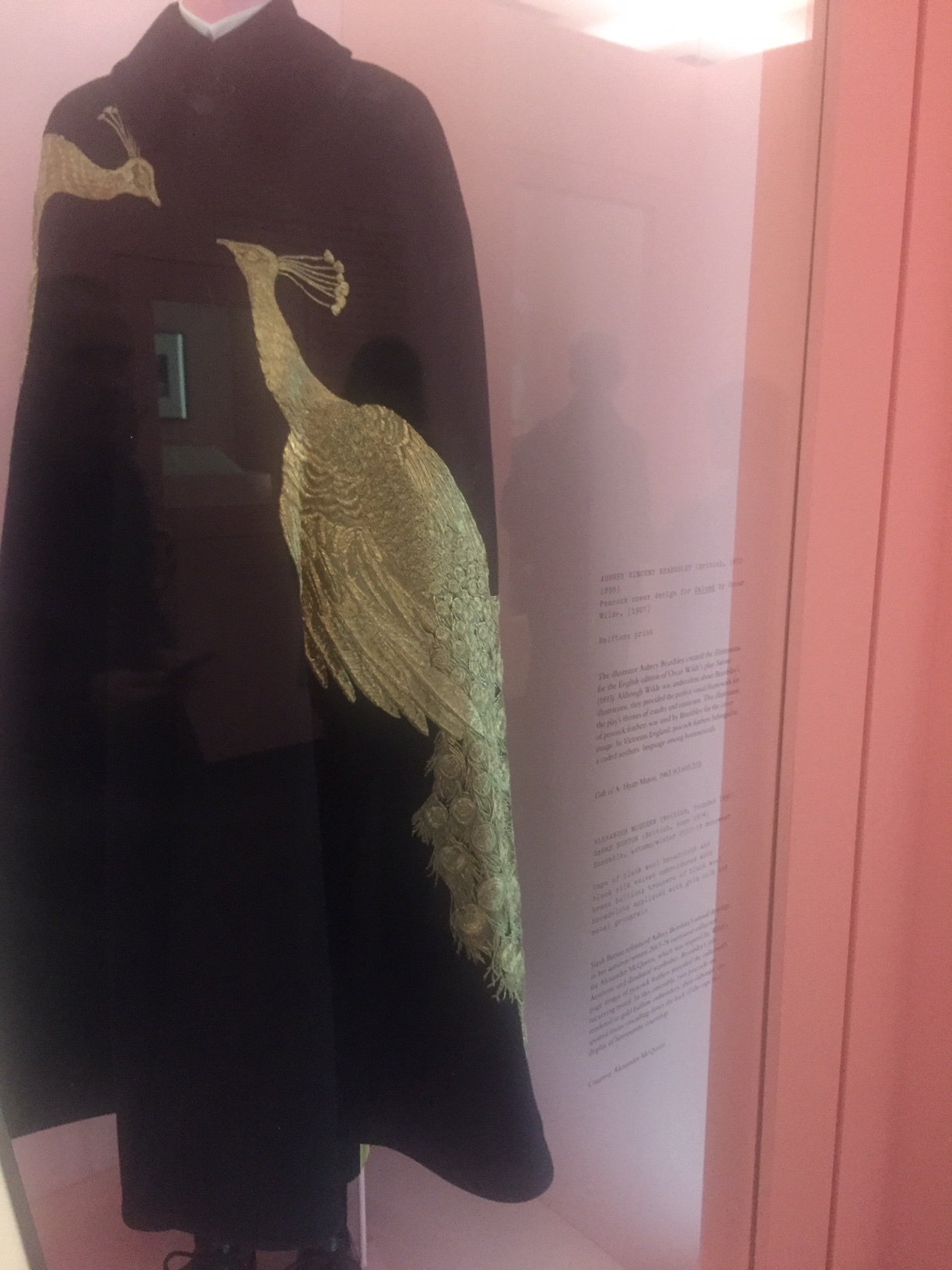

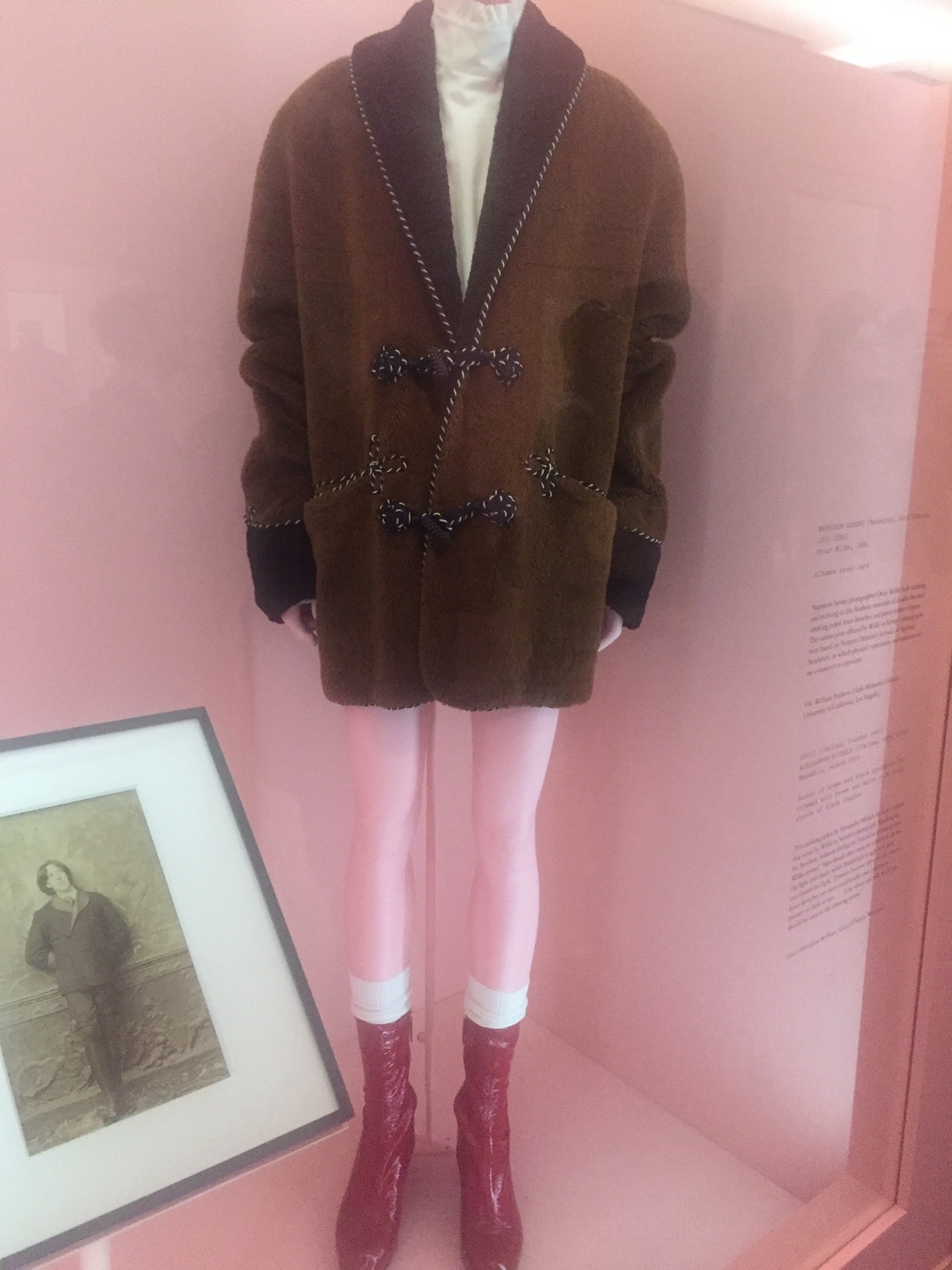

Camp morphed successively over the decades into a phantasmagoria on gay life, homosexuality, intersexuality, hermaphrodism, cross dressing, female impersonation, non binary-ism, queer aestheticism, dandyism et al. Ergo the ‘whispering’ as it was illegal to be or do any of the above until the latter part of the 20th century. Yet this vibrant multi-pronged subculture was constantly reinterpreting fashion, words, music, dance and theater. Fanny and Stella, two cross dressers figure importantly in this section as does playwright Oscar Wilde and artist Aubrey Beardsley. Rupert Everett who played Oscar Wilde in a film provides narration. These early historic sections are the most interesting of the exhibition.

A transition gallery marks the onset of Camp from the margins to the mainstream.

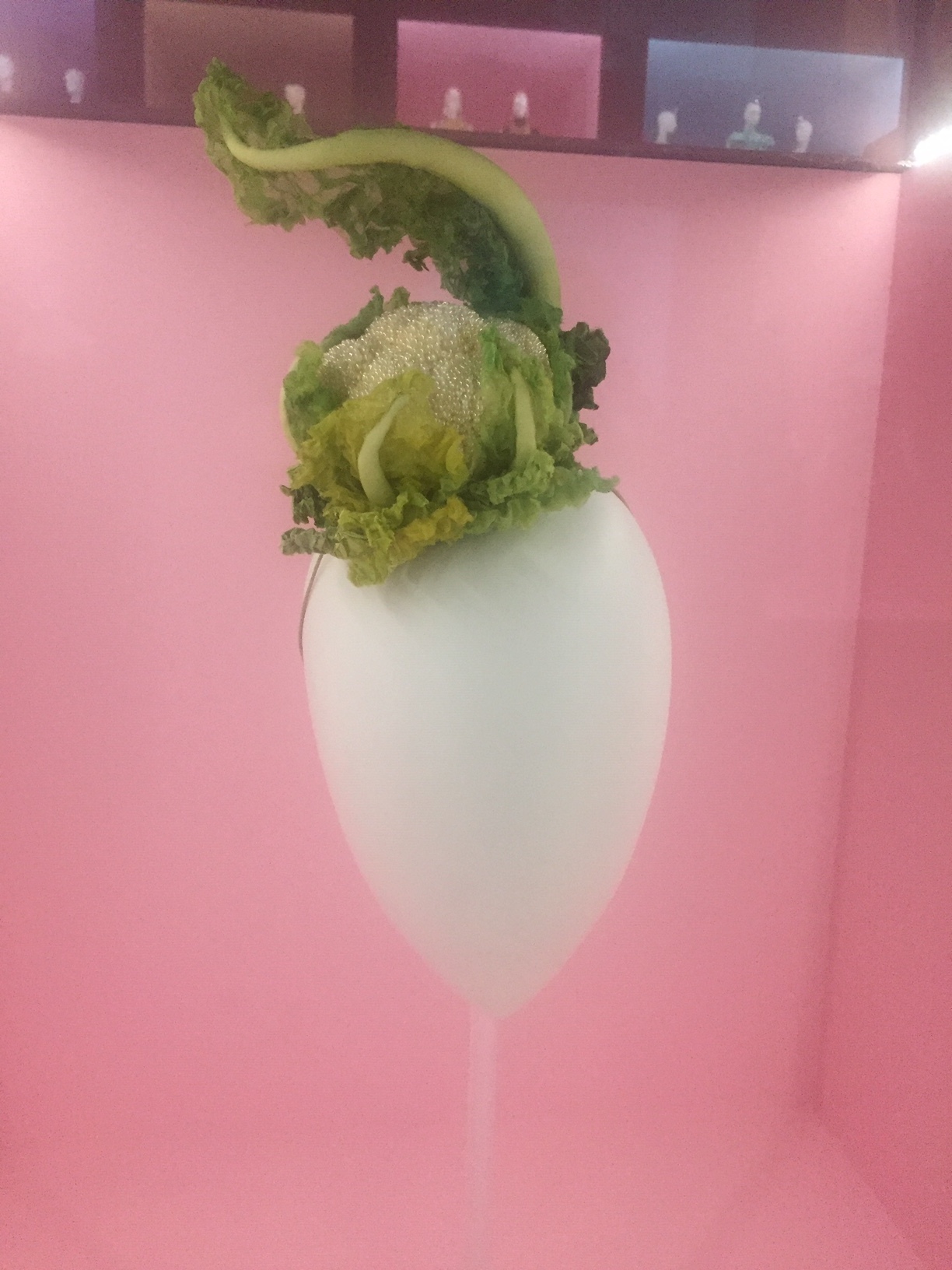

Section B, “an echo chamber” of contemporary fashion is hung in a grand double stacked display in the last large gallery. Gucci funded this exhibition so there is plenty of furry slides and as always, the curatorial eye of this section accommodates many of the designers upon whom the Institute depends for loans and support. It’s bold and colorful and a central set of vitrines isolates hats and jewels and bags. (Check out the Cauliflower hat) But one is hard pressed to understand the difference between Camp and fashion.

Christopher Isherwood separated Camp into High and Low, High having more to do with intentionality (artists) and low a more overt trolling for sex (sailors;).

Susan Sontag went further still with this differentiation of ‘naïve camp’-seriousness that fails- and ‘deliberate’ camp. Sontag is in point of fact the mannequin over which this exhibition is most fully draped.Her Partisan Review essay, Notes on Camp, which took the temperature of Camp in 1964, provides an organizing principle for many of the displays including a room in which her own essay referents from the Met are displayed. Making camp the subject of an academic essay both secured its place in the culture and made it more self-conscious. This diminished a bit of the spontaneity though none of the cleverness. A digital ticker tape of her 58 thoughts on Camp a la Jenny Holzer is the soundscape, and it’s very effective.

(An aside: I met Sontag about a decade after her essay when she was in a relationship with the actress and film producer Nicole Stephane who had appeared in Cocteau’s film Les Enfants Terribles which I didn’t see listed in this catalog but could be called Camp, along with much of Cocteau’s oeuvre. Sontag was most imposing and definitely not Camp herself. )

Homework Assignment #2:

Read Notes on Camp.

It seems like almost anything can be camp if properly framed and there the curators run into some fuzzier waters. I tried to follow Bolton’s inclusions but just as there is no one definition of camp, there is here no one narrow curatorial imperative. Camp is “irony, humor, parody, pastiche, naïveté, duplicity, ambiguity, artificiality, theatricality, extravagance, exaggeration, and aestheticism” Is the message that gay and non-binary aesthetes have been the leading edge of many artistic disciplines—something I already know and emphatically believe? That line of thinking is risky if we turn the question on its head. Is everything gay therefore Camp? A current exhibit at NYU’s Grey Art Gallery on the Art after Stonewall shows a side of gay life which is sometimes Camp but often deadly serious and tragic.

By the end of the exhibition, I came to have my own definition. Camp, as it has been presented by the Met, is a stylish, clever, often extreme riff on the themes of the day. And most important: camp makes you smile. Bravo once again to Bolton and the team. They are deeply creative and resourceful and have sealed fashion’s fate among the highest of arts. I think instead of worrying about a new building, newish director Max Hollein needs to let them have at re-installing the rest of the museum. Maybe not that much cheaper, but worth it.

Herewith a few of my own camp icons:

New York City Ballet season begins with a new spring in its step

The New York City Ballet has returned this spring under new leadership (very excited to have Wendy Whelan co-leading the company) having gone through their annus horribilis of successive #MeToos last year. For me the news that Amar Ramasar will be allowed to return is welcome—he is one of my favorite dancers. But in the meantime, men who were once eclipsed have emerged in fine fettle and a new program of ‘shorts’ ( a repeat of opening night) showed them off.

It was a Balanchine sandwich as it began with Valse Fantaisie from 1967—a pink tutu trifle that was in its time considered ‘modern’ but now feels a bit lightweight and ended with Western Symphony, something I grew up seeing at City Center which felt newly frisky and dare I say it, Camp (the Met fashion show opens this week on this theme). Highly flavored with Agnes de Mille, it was choreographed by Balanchine in 1954.

Alas despite high expectations, I was not taken with the new Pam Tanowitz Bartok Ballet which also had some equestrian flavor at the outset but then went through iterations in which I detected Irish step dancing, robots and Gold Bugs (I loved the golden bathing suit costumes however, which fit right in with the State Theater’s golden hues which are looking better and better each time I visit).

Justin Peck’s new mini-ballet Bright is a pouf of Sara Mearns loveliness but feels like an entre-acte for something down the road.

For me, the highlight of the evening was A Suite of Dances performed by Gonzalo Garcia, accompanied, on stage, by cellist Ann Kim. This Robbins piece, a solo to Bach cello variations, is so fresh and charming that it shone even, or perhaps especially, among the new work. Originally created for Baryshnikov, now performed by Garcia, an example of a longtime NYCB dancer who is just finding the spotlight, it takes on a quiet insouciance: as a musical-dance collaborator, there is nothing like Jerome Robbins. At once carefree and deep, like all of Robbins ballets it marks the looking backward-and-forwardness that characterized all his work. Often feeling jilted, on the rebound, or just plain lonely despite all his professional successes, Robbins lets that poignant quality imbue his more overtly playful hands-on-hips, pointe-to-flat choreography echoing the dichotomies of Goldberg Variations and Dances at A Gathering with which it shares an era. This is the ballet not to miss.

Photos by Erin Baiano and Paul Kolnik courtesy of NYCB.

An unusual and poignant image of Frida in pain comes to auction

Frida Kahlo underwent something like 40 surgeries to correct the cascade of physical ailments (possible spina bifida, polio, a horrendous bus collision which had driven an iron handrail into her pelvis) which tormented her but which gave her paintings, often made from her convalescent beds, a very particular vantage point and haunting quality. (Kahlo also worked with mirrors to serve as the limbs she was not able to mobilize). This photograph, which I’d not seen before, was sold at Sotheby's—as part of a Nickolas Muray collection— for 28,000 dollars.

Muray is the Hungarian born US based photographer with whom she had a decade long affair. He was married four times, Kahlo almost as many (counting the re-marriage to Diego Rivera, whom she considered her true soul mate.) but they stayed close. Frida in Traction, was taken in 1940 when Muray visited her in the hospital in Mexico, and goes tight on Kahlo’s face which allows the uncertainty of her gaze—will this surgery be the answer?—full measure. Is she accepting or fearful? The folded white cloth around her famous unibrow signifies a moment when Kahlo was incapable of facing down her legacy of pain through her art. But works made that same year which include necklaces which cut into her neck and make her bleed and hearts which are ex-corpus, show she was the eternal phoenix. Muray once wrote to her that he wished he could find “the secret how to make you well again so you could sing, and smile, love and play again as I have seen you before in the bright sun or in the dark night.” As a document of one of those times when she was not able to vanquish her pain, it is unforgettable.

Photo by Nickolas Muray; © Nickolas Muray Photo Archives

The San Francisco Maritime Museum: a hidden WPA gem is revitalized

The story of the San Francisco Maritime Museum, a hidden San Francisco gem, is not just one of architecture and design although that is what pops when you walk in the subterranean Ghirardelli Square-adjacent entrance. Looking out over the historic seafaring vessels of the Hyde Street Pier and the crescent shaped beach that could easily be mistaken for Miami, a visitor is struck by the graciousness of this temple to the history of West Coast Maritime History, rich with exhibits that speak of the life of the people who made their living at sea. Unlike the more famous Coit Tower however, also a product of WPA largesse, the Maritime Museum has been very much under the national radar until now. Built in 1939 jointly by the WPA and the City of San Francisco as a bathhouse, the museum is part of a National Park Service Maritime Historical Park that highlights the city's connection to the sea.

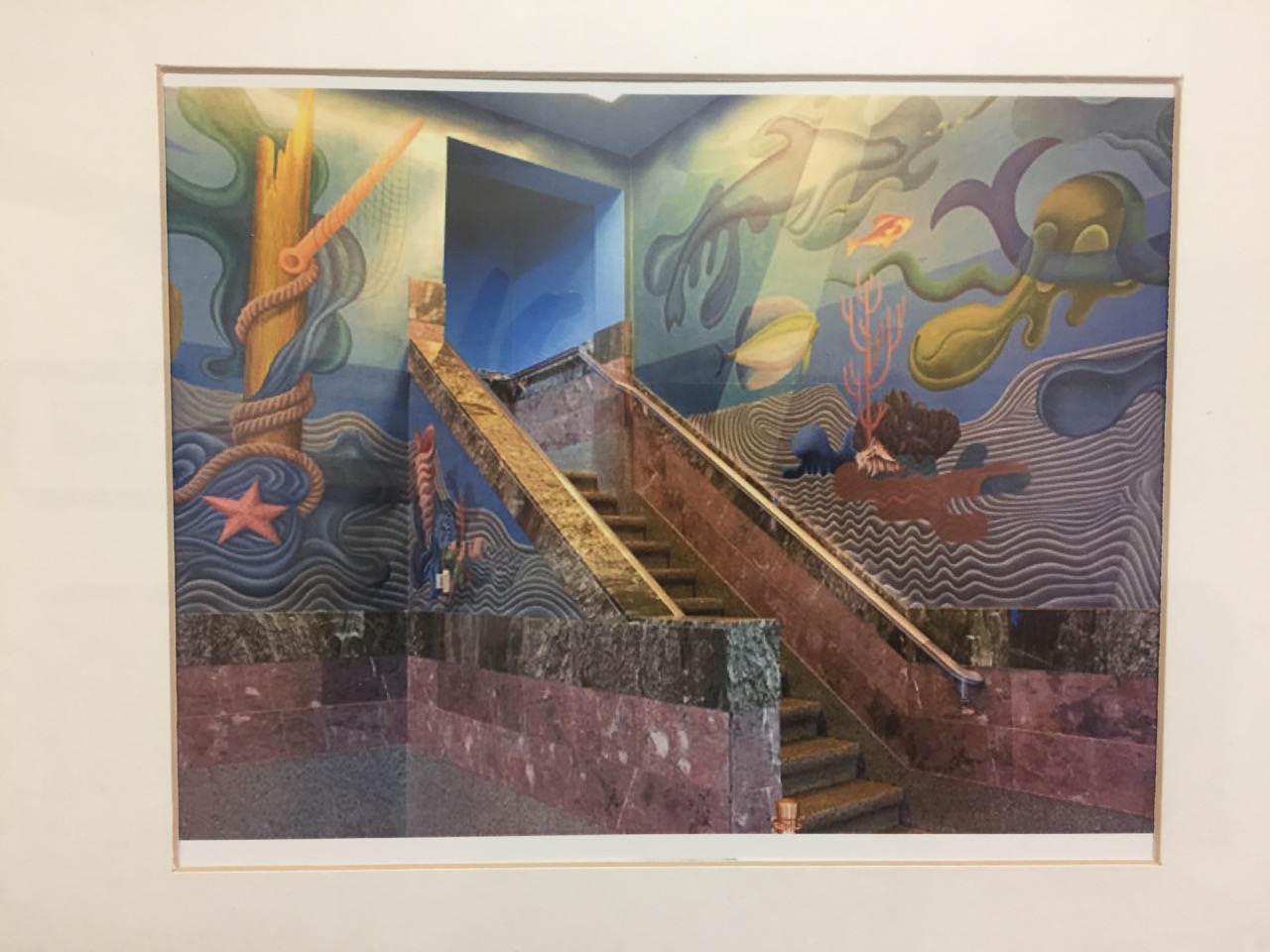

Though the exhibits fascinate, inevitably, what thrills are the sublime murals, tilework and paint fantasia that are the work of WPA artists, each with a very different background whose work combines to make this space as dynamic and important as any art moderne building in the world.

It is the characters and practices of these artists, their personal histories and lives, that make this building very special, easily as impressive as the Coit Tower. This weekend, the Museum reopens with a second floor of maritime themed murals which complement the first floor’s showier ones and a third floor of exhibits tracing the history of the building.

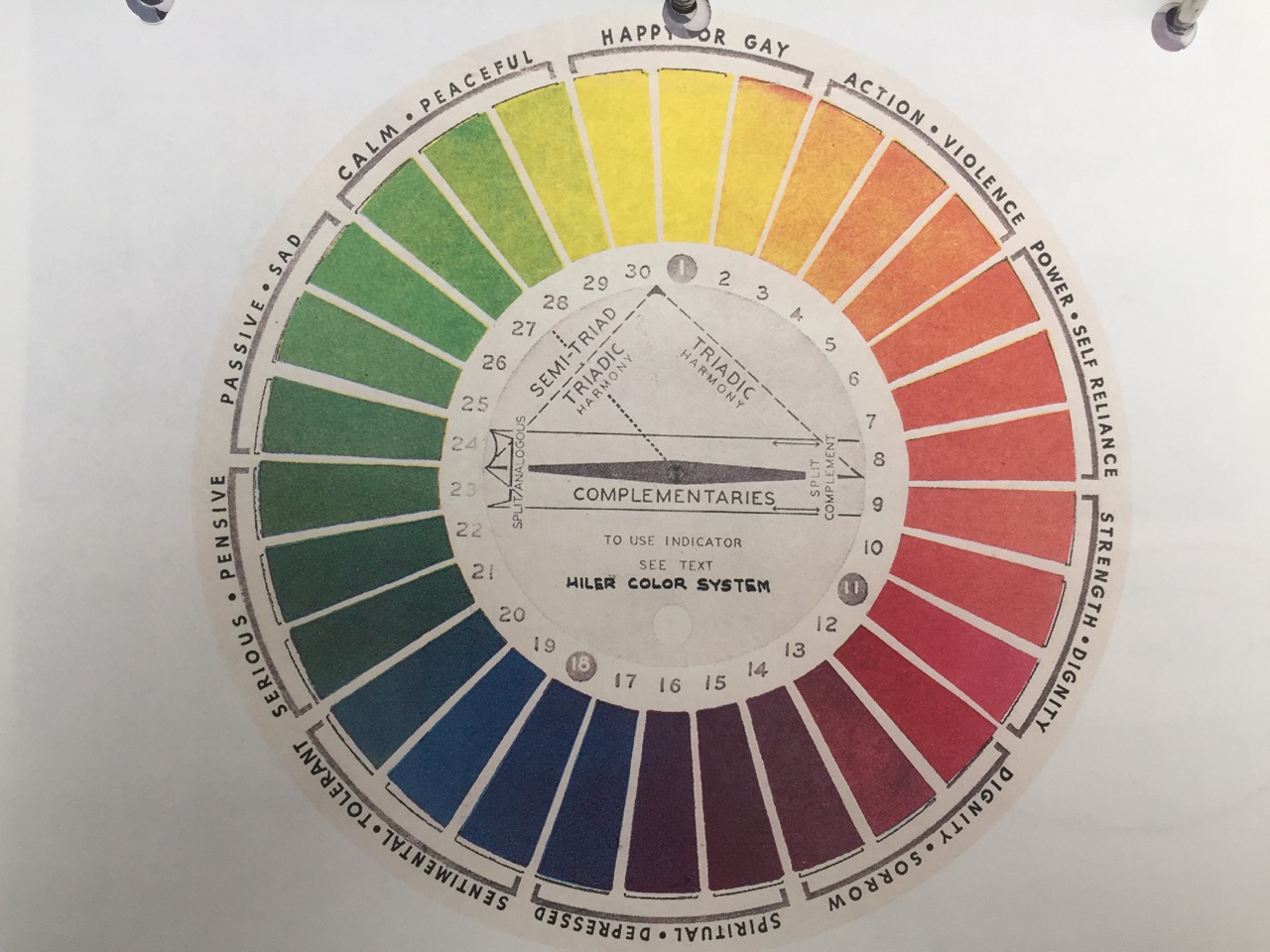

The whole project came to fruition over more than four years under uber-artist Hilaire Hiler who not only did the phantasmagoric first floor murals of the Lost Cities of Atlantis and Mu but supervised the other floors and artists and was the liaison to the architect. Hiler, a Jewish, 6 foot hulk from Minnesota who had his ears pinned back in an effort to appear smaller, was an American artist and color theoretician, a polymath who also wrote a bibliography of costume, worked as a set designer and jazz musician and whose psychoanalytic training became the underpinning of much of his work. He attended RISD and became one of the many Parisian expats, befriending Henry Miller and Anais Nin and Hemingway among others at the Jockey Club in Paris where he was a host and was often seen out and about with his pet monkey. His ‘neonature' theories about art found supporters in Miller and William Saroyan and one ceiling, the Prismatarium” is an ode to his color theory in which he proposed that color and the human psyche interact to enhance creativity. He had a long, eccentric and distinguished career including a stop in Hollywood and a collaboration with Rene D'Harnoncourt in San Francisco. He was authoritarian but respected his fellow artists as they collaborated on the design of the over 20,000 square feet of the elegant building.

Sargent Johnson, once a prominent black sculptor, painter and ceramicist and Communist of African American, Cherokee and Swedish descent who designed the mosaic tile murals was inspired by the work of Diego Rivera, Jose Orozco and David Siquieros.. His mosaic tile murals in shades of sea greens which grace the rear exterior deck overlooking the bay and his green carved slate which adorns the building entrance are further delights. Johnson had been orphaned as a child and grew up in asylums. He was born in the east but came to San Francisco to study and was employed by the WPA on a number of projects in a supervisory role. He had a small retrospective in Oakland in the 70s. He is lumped in with the Harlem Renaissance but in fact made his own way in the west. He was an artist who wanted above all 'to show the Negro to himself" even though he was half white.

Richard Ayer was charged with the newly refurbished second floor murals. The themes are nautical like puzzles which refer to abstractions of boat rigs, pressure points, wave patterns, plimsall, davits, signal rockets, naval arches, wireless hookups interspersed with wave forms, fish, spars, sea fowl. There are 5 shades of marine color and abalone shells in the terrazzo floor. Ayer used a novel technique called Polychrome Bas-Relief which allowed for raised areas depicting anchors, coral beds and birds. Artist Shirley Staschen, who had also done the WPA murals at the Coit Tower worked on the second floor murals with him.

Despite the fact that the WPA was meant to give work to American artists, many immigrants got involved when specialities were called for. An Egyptian tile worker custom cut and lay the tilework which was fabricated locally. Anna Medalie, Russian-born, assisted in the gold leaf and glazing on the first floor. (Women were largely equal partners at the WPA.) Benjamin Bufano, an Italian did most of the free standing sculpture. The socio-political values of the artists mandated that the space be open to the "public". They protested and walked off the job when they feared it might become too exclusive.

The basement or ground floor was the beachgoers entrance, through turnstiles and a newly invented system of sanitization including foot baths and automatic sensors that turned on the showers, stainless baskets to keep clothing, one room each for boys, girls, women, men.

Upstairs a radio room with vintage equipment has been reconstructed.

The structure, once referred to as a ‘Casino’ at which elegant parties and dinners were often held has gone through a number of iterations, but is now a monument to the life of the sea--the seductive, watery depths below abundant with marine life, the boats and tools of the trade at eye level--and to modernity, and to the WPA and its profound importance in our cultural history.This whole notion of public access and innovation is a testament to the way the federal government, when its working properly, can utilize the arts for the benefit of the public as no other entity can. The Park Service has been working for years on this new restoration and I could not think of a finer place for my tax dollars.

Images courtesy National Park Service, San Francisco Maritime Museum and the author

Goddesses at the Met

Inlaid with rubies in her eyes and navel as was the occasional special custom for Mesopotamian deities, this petite, exquisite 1st century BC-1st century AD standing nude statue in the Met Museum’s World Between Empires show of Middle Eastern treasures—and their horrific destruction by Isis--raises questions of divine identity. Is she a Greco-Roman Venus goddess of beauty and love or, as one curator suggests, Ishtar of Babylon who was closer to home? One other similar example of this kind of statue lay on her side easily recalling the many Olympias of the 19th century. Having just attended a Paola Antonelli salon at MoMA on ‘White Men”, I wondered why alabaster queens were the symbol of a middle eastern cultures? The statue is on loan from the Louvre where even in her diminutive state she could outshine the Mona Lisa

Images courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

White Men: a MoMA salon confronts the status quo

On the heels of Donald Trump’s almost vindication by the special prosecutor, curator Paola Antonelli’s Salon at MoMA about White Men held a special charge. One panelist, Whitney Dow is making films and interviewing only white men so they are not afraid to speak out. This image was offered by panelist Aruna D’Souza as a more ironic version of co-panelist Rich Benjamin’s slicing and dicing of white men into four categories: entrepreneurs, environmentalists, working men and minstrels with examples--besides Trump-- like Beto O’Rourke, who in his opinion are allowed to fail upward as no others. As was pointed out by almost all the speakers, white guys are still running and populating things--Silicon Valley, Washington, the Environment, Wall Street, Museums and Culture, and so it takes a lot of heft to move them from their special, centuries-long perch on high. The artist, Pastiche Lumumba, has nailed it in a “Woke, Gentrifyer Starter Pack” with copies of the right magazine, the right beer, the right tech, the right music….etc. It was a rare humorous moment in an evening which shone a light on privilege, race, gender. It’s very hard in the art world right now to escape this kind of categorization which I understand comes from a place of deep disaffection with the way things are. (I repost Paola’s reading list) As a white woman, too, I’m hardly exempt but I can speak to more personal issues having spawned four of them. I once wrote a whole book about having felt like I landed on an alien planet and barely lived to tell the tale.

Reading List and image courtesy of Paola Antonelli, MoMA Salons

Discovering Masculinity & White Identity

-Bazelon, Emily, White People Are Noticing Something New: Their Own Whiteness, The New York Times Magazine (06.13.2018

-Fortin, Jacey, Traditional Masculinity Can Hurt Boys, Say New A.P.A. Guidelines, The New York Times (01.10.2019)

-McGill, Andrew, Why White People Don’t Use White Emoji, The Atlantic (05.09.2016)

-Roberts, David, American white people really hate being called “white people”, Vox (07.26.2018)

-Whitaker, Robyn J., Jesus wasn’t white: he was a brown-skinned, Middle Eastern Jew. Here’s why that matters, The Conversation (03.28.2018)

-Yancy, George, #IAmSexist, The New York Times (10.24.2018)

-Harmful masculinity and violence, American Psychological Association (2018)

White Male Entitlement

-Cole, Teju, The White-Savior Industrial Complex, The Atlantic (03.21.2012)

-Fleming, Peter and Rhodes, Carl, CEO pay is more about white male entitlement than value for money, The Conversation (07.23.2018)

-Hall, Ronald E., Entitlement Disorder: The Colonial Traditions of Power as White Male Resistance to Affirmative Action, Journal of Black Studies, 34:4, 562-579 (03.2004)

-Keltner, Dacher, Sex, Power, and the Systems That Enable Men Like Harvey Weinstein, Harvard Business Review (10.13.2017)

-Lissner, Caren, Men are Killing Thousands of Women a Year for Saying No, Dame (10.24.2017)

-Rosner, Helen, Mario Batali and the Appetites of Men, The New Yorker (12.13.2017)

Maintenance of White Privilege & Benefit of the Doubt

-Lerer, Lisa, The Privilege of Being Beto, The New York Times (03.11.2019)

-McIntosh, Peggy, White Privilege and Male Privilege: A Personal Account of Coming to See Correspondences Through Work in Women's Studies, Wellesley College Center for Research on Women (1988)

-Onion, Rebecca, Automatic for the People, Topic Magazine (2018)

-Stack, Liam, Light Sentence for Brock Turner in Stanford Rape Case Draws Outrage, The New York Times (06.06.2016)

-Wurtenberg, Nathan, Gun Rights are about keeping White Men on Top, The Washington Post (03.09.2018)

-Yancy, George, Dear White America, The New York Times (12.24.2015)

Power & Normativity

-Amatulli, Jenna, Donald Glover Needed ‘White Translator’ To Convince FX To Allow ‘N-Word’ In ‘Atlanta’, HuffPost (02.27.2018)

-Friedman, Vanessa, Fashion’s Woman Problem, The New York Times (05.20.2018)

-Golliver, Ben, LeBron James calls NFL owners 'old white men' with 'slave mentality' toward players, Chicago Tribune (12.22.2018)

-Grigsby Bates, Karen, 'A Chosen Exile': Black People Passing In White America, NPR (10.07.2014)

-McCarron, Meghan, When Male Chefs Fear the Specter of ‘Women’s Work’, Eater (11.30.2017)

-Walker, Tim, Quentin Tarantino accused of ‘Blaxploitation’ by Spike Lee... again, Independent (12.26.2012)

White Men in the Workplace

-Cain Miller, Claire; Sanger-Katz, Margot; Quealy, Kevin, The Top Jobs Where Women Are Outnumbered by Men Named John, The New York Times (04.24.2018)

-Dishman, Lydia, White men still hold the most leadership positions in tech, Fast Company (06.25.2018)

-Jones, Stacey, White Men Account for 72% of Corporate Leadership at 16 of the Fortune 500 Companies, Fortune (06.09.2017)

-Weber, Lauren, White Men Challenge Workplace Diversity Efforts, WSJ (03.14.2018)

-White, Gillian B., There Are Currently 4 Black CEOs in the Fortune 500, The Atlantic (10.26.2017)

White Male Anxiety & Perceived Discrimination

-Dr. Agarwa, Pragya, Unconscious Bias: How It Affects Us More Than We Know, Forbes (12.03.2018)

-Berman, Jillian, When a woman or person of color becomes CEO, white men have a strange reaction, MarketWatch (03.03.2018)

-Berman, Jillian, White men who can’t get jobs say they’re being discriminated against, MarketWatch (06.17.2018)

-Blow, Charles M., White Male Victimization Anxiety, The New York Times (10.10.2018)

-DiAngelo, Robin, White Fragility (Chapter), International Journal of Critical Pedagogy, 3:3, 54-70 (2011)

-DiMuccio, Sarah and Knowles, Eric, How Donald Trump appeals to men secretly insecure about their manhood, The Washington Post (11.29.2018)

-Haider, Mischa, The Next Step in #MeToo Is for Men to Reckon With Their Male Fragility, Slate (01.23.2019)

-Massie, Victoria M., Americans are split on "reverse racism." That still doesn't mean it exists, Vox (06.29.2016)

-Norris, Michele, As America Changes, Some Anxious Whites Feel Left Behind, National Geographic Magazine (04.2018)

-Price, S.L., Whatever Happened to the White Athlete?, Vault, Sports Illustrated (12.08.1997)

-Bird: NBA 'a black man's game', ESPN (06.10.2004)

White Male Pride & White Male Rage

-Cep, Casey, The Perils and Possibilities of Anger, The New Yorker (10.15.2018)

-Deitsch, Richard, Anger Therapy in his Autobiography John McEnroe Comes Clean about his On-Court Behavior and Off-Court Anguish, Vault, Sports Illustrated (06.24.2002)

-Fortgang, Tal, Why I'll Never Apologize for My White Male Privilege, Time (05.02.2014)

-Friedersdorf, Conor, Does ‘White Male Rage’ Exist?, The Atlantic (10.10.2018)

-Krugman, Paul, The Angry White Male Caucus, The New York Times (10.01.2018)

-Newman, Brooke, The Long History Behind the Racist Attacks on Serena Williams, The Washington Post (09.11.2018)

-Schwartz, Alexandra, Brett Kavanaugh and the Adolescent Aggression of Conservative Masculinity, The New Yorker (09.27.2018)

Insecure Responses to our First Black President

-Coates, Ta-Nehisi, The First White President, The Atlantic (10.2017)

-Edsall, Thomas B., The Fight Over Men Is Shaping Our Political Future, The New York Times (01.17.2019)

-Lopez, German, The past year of research has made it very clear: Trump won because of racial resentment, Vox (12.15.2017)

-MacWilliams, Matthew; Nteta, Tatishe; Schaffner, Brian F., Explaining White Polarization in the 2016 Vote for President: The Sobering Role of Racism and Sexism, presentation at the Conference on The U.S. Elections of 2016: Domestic and International Aspects, January 8-9, 2017 (2017)

-Serwer, Adam, Trumpism Is ‘Identity Politics’ for White People, The Atlantic (10.25.2018)

A ‘Rebranding’ of White Male Identity

-Benjamin, Rich, The Trumpist White Minstrel Show, Los Angeles Times (10.27.2018)

-Blow, Charles M., ‘The Lowest White Man', The New York Times (01.11.2018)

-Gold, Michael, ‘I Just Love White Men’: White Man Aims Racist Rant at Columbia Students of Color, The New York TImes (12.11.2018)

-Hesse, Monica, How should we talk about white men today, The Washington Post (02.13.2019)

-Mishra, Pankaj, The Religion of Whiteness Becomes a Suicide Cult, The New York Times (08.30.2018)

-Percy, Jennifer, The Life of an American Boy at 17, Esquire (02.12.2019)

Policing the Bounds of the White Patriarchy

-Anderson, Elijah, “The White Space”, American Sociological Association, Sociology of Race and Ethnicity, 1:1, 10–21, (2015)

-Gilio-Whitaker, Dina, Settler Fragility: Why Settler Privilege Is so Hard to Talk About, Beacon Broadside (11.14.2018)

-Harris, Cheryl I., Whiteness as Property, Harvard Law Review, 106:8, 1707-1791 (1993)

-Menand, Louis, The Supreme Court Case That Enshrined White Supremacy in Law, The New Yorker (02.04.2019)

-Onwuachi-Willig, Angela, Policing the Boundaries of Whiteness: The Tragedy of Being out of Place from Emmett Till to Trayvon Martin, Berkeley Law Scholarship Repository (2017)

-Patton, Stacey, White Women aren't Afraid of Black People, They want Pretty Power, Dame (07.30.2018)

-Wildman, Stephanie M.,The Persistence of White Privilege, Washington University Journal of Law & Policy (01.2005)

The White Male Online

-Angwin, Julia and Grassegger, Hannes, Facebook’s Secret Censorship Rules Protect White Men From Hate Speech But Not Black Children, ProPublic (06.28.2017)

-Collin, Rowan and Petray, Theresa L., Your Privilege Is Trending: Confronting Whiteness on Social Media, Social Media & Society (05.17.2017)

-Donovan, Joan, How Hate Groups’ Secret Sound System Works, The Atlantic (03.17.2019)

-Iqbal, Nosheen, Donna Zuckerberg: ‘Social media has elevated misogyny to new levels of violence’, The Guardian (11.11.2018)

From White Supremacy Ideology to Violence

-Bouie, Jamelle, The March of White Supremacy, From Oklahoma City to Christchurch, The New York Times (03.18.2019)

-Bowles, Nellie, ‘Replacement Theory,’ a Racist, Sexist Doctrine, Spreads in Far-Right Circles, The New York Times, (03.18.2019)

-Coaston, Jane, The New Zealand shooter’s manifesto shows how white nationalist rhetoric spreads, Vox (03.18.2019)

-Garcia-Navarro, Lulu, White Supremacy And Terrorism, NPR (03.17.2019)

-Kaadzi Ghansah, Rachel, A Most American Terrorist: The Making of Dylann Roof, GQ (08.21.2017)

-Parrott, Joseph, R., How white supremacy went global, The Washington Post (09.19.2017)

-Pazzanese, Christina, Probing the roots and rise of white supremacy, The Harvard Gazette (03.18.2019)

-Singal, Jesse, Undercover With the Alt-Right, The New York Times (09.19.2017)

-Williams, Jennifer, White American men are a bigger domestic terrorist threat than Muslim foreigners, Vox (10.02.2017)

Watch

-Benjamin, Rich, WHITOPIA: An Improbable Journey to the Heart of White America, Youtube (01.25.2016)

-Blanco, Mykki, WYPIPO: Mykki Blanco speaks about race in whiteface, Dazed (08.23.2018)

-Dow, Whitney, Whiteness Project, ongoing

-Rankine, Claudia, The Fire This Time: Claudia Rankine on Whiteness as a Brand, The New Yorker Festival (10.12.2015)

-Welp, Michael, White Men: Time to Discover Your Cultural Blind Spots, TEDxBEND (07.06.2017)

-Videos Show a Collision of 3 Groups That Spawned a Fiery Political Moment, The New York Times (01.22.2019)

-What's Killing America's White Men? BBC News, BBC News (10.18.2018)

Mary Quant at the V and A

A Mary Quant retrospective opens in London at the V and A today. Along with Biba, her stores were THE place to get your clothes. Quant was designing in the height of the sixties- The Doors, The Stones, the Beatles and Hendrix all released new albums. But at the same time the Apollo 1 astronauts went up in flames, we doubled down in Vietnam, and the middle east erupted in the Six Day War. Quant was untrained but understood that stretchy knits and tights were the way forward.

Image courtesy the V and A

The Brant Foundation reminds when art was the thing

In the midst of all the brouhaha about architecture gone wrong from coast (Hudson Yards) to coast (Lacma), the new Richard Gluckman building for the Brant Foundation in New York stands as a model of discretion and an excellent showcase for art. Remember when the art was the thing? The ceiling pool that greets you in the brick walled space feels like a dreamy light filled upside-down Turrell rather than a gimmick, you’re underwater without having to hold your breath. Gluckman has taken many inspirations from the mid century (Quincy Jones?)—the mullioned windows, the white birch landscape, the decomposed granite hardscape—and the wood plank or brutalist ceilings (Mendes da Rocha?) and supersized them made them neater and grander, but still, dare I use this word, tasteful. The view from the top 4th floor in particular is neatly centered on a church spire and the Manhattan one sees is not the new pencil thin spires dotting the island but rather the humbler East Village of yore. The Basquiats are plentiful and look very well in the space, especially enchanting when hung salon style downstairs, and a friend and I calculated that he was only in his early twenties when many of them were painted. They feel electric —a young black prodigy whose time was over too fast communing with Walter de Maria who had repurposed a ConEd station for his studio. Basquiat’s capabilities as a wordsmith—he almost seems to playing a version of Jotto with himself—also come to the fore. It was a pleasure to like something so unreservedly for a change.

Entre Tu y Yo: Soledad Barrio and Noche Flamenca return

Soledad Barrio has rightfully received glowing notices for her current production Entre Tu y Yo at the Connelly Theater (a beautiful repurposed opera house), but it is the joyful energy of the entire cast of Noche Flamenca, her troupe, which has risen exponentially to her demanding level. The interaction among the singers (Manuel Gago, Emilio Florido, Carmina Cortes), the musicians (Salve de Maria, Eugenio Iglesias, David Rodriguez) and dancers (Antonio Rodriguez, Jasiel Sierra, Marina Elana, Soledad) is both playful and heartfelt, a true tonic in these dark and twisted times.

Soledad’s Solea, the final palo, is one of her signature dances, and is always perfection. But it is in her duet with Elana that flamenco is newly relevant. Though Arthur Schnitzler’s La Ronde is credited as being the inspiration for this series of duets and trios in the program, this vignette jumped out immediately as being a riff on Ingmar Bergman’s film Persona. Sure enough, artistic director Martin Santangelo, the co-choreographer of the piece with Soledad, confirmed that this segment indeed sprang from their watching the film over and over again and being touched by the haunting images of the two women in dialogue with each other and with themselves. What do we see in the mirror? The film reminds us that the role of carer and patient, of language and silence, of identity itself, is fluid and malleable.

What better form to capture these complex themes than flamenco? One of the first things a flamenco student learns is the simple—but technically challenging— ‘in’ or ‘out’ of the rotation of the hand and fingers. Each finger must be articulated as the wrist leads the way. The choice of whether to go ‘in’ or ‘out’ can be a choreography but also an emotion. It would not be stretching it to say that each movement of this intricate discipline seems to have an equal and opposite force. Soledad—also an exacting teacher—prizes the compactness of a turn, the full arch of a back, swan-like extension of the arms —and brings these fundamental dualities to the surface in a kindred twinning with Persona. Are we ‘in’ or ‘out’?

It is rare to see such an intimate flamenco dance for two women, and I heard some fellow flamencos referring to it as a ‘lesbian’ dance. Of course everyone is free to interpret as she wishes, but this felt a reductive rendering. The costumes are simple black leatherette pants and silken shirts and this contemporary look coupled with the dancers intricate and intimate engagement with each other stripped away superfluous style. The piece feels absolutely essential.

The production runs through the end of March.

Photos by Elaine Graham and Peter Graham courtesy Noche Flamenca

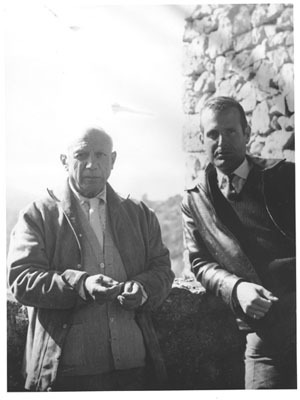

John Richardson dies at 95, a biographer of Picasso equal to his lifelong subject

The following is an excerpt from my Huffington Post piece on Volume III of Richardson’s Picasso biography.

…All the more reason then to be worshipful and impressed at the astounding work of John Richardson who has produced the third volume of his biography of Picasso, The Triumphant Years, published this week to great acclaim. Richardson’s unflagging erudition, meticulous reporting, insatiable digging, clever connections, and vast and deep personal knowledge of the players makes this series much closer to a performance piece of biography , the definitive text.

And because Richardson makes it perfectly clear with engaging narrative and precise scholarship how worthy his subject is, even those who have read about Picasso before will be newly swept away by the intricacies of this complex character. This is not, however, just a tome for insiders, though it helps to have a healthy interest in art and artists.

Richardson met Picasso while living with Douglas Cooper (who had himself wanted to write the biography) in the south of France and saw him regularly from the early fifties through the early sixties. He began by thinking he would write about the wives and mistresses of Picasso, the way the artist used art and sex, painting and making love, as metaphors for each other and how the style of his work changed as he changed women—volatile relationships that Dora Maar, herself one of the mistresses, characterized to him as ‘first, the plinth, then the doormat”. This was the template we used on the film, (WNET, Picasso, A Painter’s Diary) and it’s reductive and catchy, certainly one way to process the gargantuan archive when you only have ninety minutes.

But as Richardson himself says, “Picasso’s work is far too protean and paradoxical to be limited to a single reading.” And so he abandoned that seductive narrowcasting at the outset in favor of a much more comprehensive and penetrating approach.

One that would more or less take the rest of his life.

Richardson isn’t the first to devote most of his life to Pablo, as the volumes make clear. The Picasso bibliography includes everything from kiss and tells to scholarly treatises about the work and any number of memoirs and biographies. (Richardson is impatient and dismissive of some of these earlier efforts, calling them everything from “unreliable” to “rigamarole” or “fairy tale” to outright “wretched” or “sheer fantasy”.) But his end result is entirely different. Encyclopedic without being boring, any future artist’s biography, or really any biography, will inevitably have to step over Richardson’s very high bar.

Occasionally, biographers manage to be fans of their subjects for the duration. It’s hard to love someone unreservedly whom you come to know so intimately— Richardson doesn’t shy away from scandal, rather he is propelled by it, and sometimes, if this works to Picasso’s disadvantage, so be it. Looking at a life from the perspective of the warts and all can produce battle fatigue but at the end of the third volume (the ballets, the project for a memorial to Apollinaire, the bourgeoise life with Olga, the flirtation with Sara and Gerald Murphy, the rebellious hedonism of his attraction to the seventeen year old Marie Therese) with Picasso shrugging off Surrealism and heading for the shattering Guernica, one still feels Richardson’s magnificent enthusiasms for the moods, the settings, the entourages that may have influenced him; the motivations, the myth-busting, the sexual/historical/empirical digressions often taking us far afield only to bring us back a bit later with a much richer understanding of what made this man, and his world, tick.

The volumes look and are dense, (Volume 1 ranges from 1881-1906, Volume 2 from 1907- 1916 and Volume 3 from 1917-1932) but they are intensely readable—chatty, personal, with mini- biographies of others in the Picasso circle—so that we come to know just how convoluted and complex the roots of the art were with Pablo often devouring the hands that were feeding him. The tangents, however “vaut le detour” and are every bit as juicy as the three star view of the man himself. Often, Richardson makes patently clear, Picasso was conceptually leagues ahead of everyone else. But at times he was in debt to other geniuses who were his friends and competitors-Braque, Gaugin, Matisse, Seurat—and to the other protean talents from whom he freely stole(Manet, Ingres) ideas and images.

The normally heavy lifting of biography thus seems like gossamer in his hands, the facts arranged in such a way as to ease you on down the road with the tone of a confidence or a wink. The iconography of each important work is disarmingly traced, threading the personal and professional antecedents into one comprehensive whole. There are no sacred cows for Richardson—and like a cat he sneaks up and circles the truth and then pounces on it, explaining the artistic breakthroughs, the changes from one style to another, the sexuality and drugs which fueled some of them, and Picasso’s own drama-king ego that self-mythologized to the point that he came to believe in the stories too. As a myth debunker Richardson, however, is unsurpassed, adroit at peeling the layers: first, those of Picasso himself, then the second generation contemporary witnesses who often rewrote history, then the third generation anecdotal whispers, the fourth generation scholarly reckoning, and so on, often a daisy chain of prior confabulation.

Richardson leaves no dwelling, no voyage, no influence (the wonders he saw and appropriated into his own work), no woman, no friend , or enemy uncharted. One resists the tendency to makes lists only with difficulty: the houses (in Volume Three alone: Montrouge, rue la Boetie, le Gueridon, La Vigie, la belle Rose, la Haie Blance, Boisgeloup), the Women (madcap Fernande, lissome Eva, bourgeoise Olga, , sexpot Marie Therese, free spirited Francoise, imposing Jacqueline), the friends (Apollinaire, Cocteau, Jacob, Breton, Gertrude Stein, Stravinsky, Diaghilev) and the enemies and some that straddled the two camps, the Dealers (Kahnweiler, Rosenberg), the ballets (Parade, Tricorne, Pulcinella, Mercure, L’epoque des Duchesses, La Danse), the Museums, (besides Paris, Antibes, Barcelona and now Malaga) the Galleries, the retrospectives and exhibitions, the media (paint, sculpture, photography, poetry, collage, tapestry). All come under his watchful, painstaking and often bemused eye.

Richardson’s gift for language also has the added bonus of a mini-tutorial in French and Spanish slang —gratin (high society), bien couillarde (ballsy, or well hung), tertulia (group of friends).

And as far as wrangling goes, Richardson is unrivaled. Some of the images were a revelation to me; many classified or in private collections that were being carefully concealed at the time of the documentary but his long personal cultivation of so many of the Picasso personages has reaped its rewards and the astonishing selection of photographs from the Olga years in Volume Three is testament to this.

Richardson notes that for most of his life, Picasso was already in the spotlight, that the tributes and retrospectives one normally gets at the end had been ongoing since his twenties. Little details, why Picasso’s black was blacker than black (he added silver powder) or his relationship with Chanel (one night stands) make the reading lively. But it also helps to be reminded of his early genius, the sheer power of his intellectual and instinctive audacity—the breakthrough Demoiselles D’Avignon for example,was painted when he was 25!

In short, Richardson seems to have found a way to see Picasso plain while at the same time respecting his obviously century-dominating genius. Fernande, an early “official” mistress apparently said, “He who neglects me, loses me” and Picasso might well have intimated the same thing. Fear not, Richardson has made amply sure we won’t.