I’ve fallen in love with Benedetta Cappa--one half of the Marinetti couple from the Lucia Re Magazzino Museum lecture series--but as compelling as her more famous husband.

Benedetta was a student of Giancomo Balla, Futurist par excellence, but when she met Filippo Marinetti, the two were forever conjoined in love and art. Benedetta experimented with many art forms, and was an intriguing writer, but it is her colorful paintings that we might know best.

Contemporary of Hilma Af Klint and Agnes Pelton, Benedetta’s work has synergies that recall these other artists yet I don't know of a time when they might have seen each other's work.

She and Marinetti birthed Tactilism--which was a multi dimensional production of objects that took Futurism to the third dimension. It sounds like an early virtual reality experience, "to perfect spiritual communication between human beings, (get this) through the epidermis". (This reminded me of the moment in ET when the beloved space creature sticks out his finger.)Benedetta--who jettisoned her surnames as she came into the fullness of her own self--went on to promote Aeropainting along with her husband and Balla and others. All in all, a very modern woman.

Her Palermo post office murals were the piece de resistance of the Guggenheim Futurist exhibition a few years back. But she is still less known than the other two women who have been subjects of recent solo exhibitions.

The Inside World of Alice Neel

Though I had seen many images from the Alice Neel show at the Met, I was not prepared for the breadth and depth of the actual exhibition. Fair warning: even with a ticket, in mid week, in the morning, the line was at least 30-45 minutes to enter. It is beyond worth it.

The exhibition provokes questions about her biography. If you go to aliceneel.com, you will be able to see marvelous photographs of her and her world and also learn the more granular details.

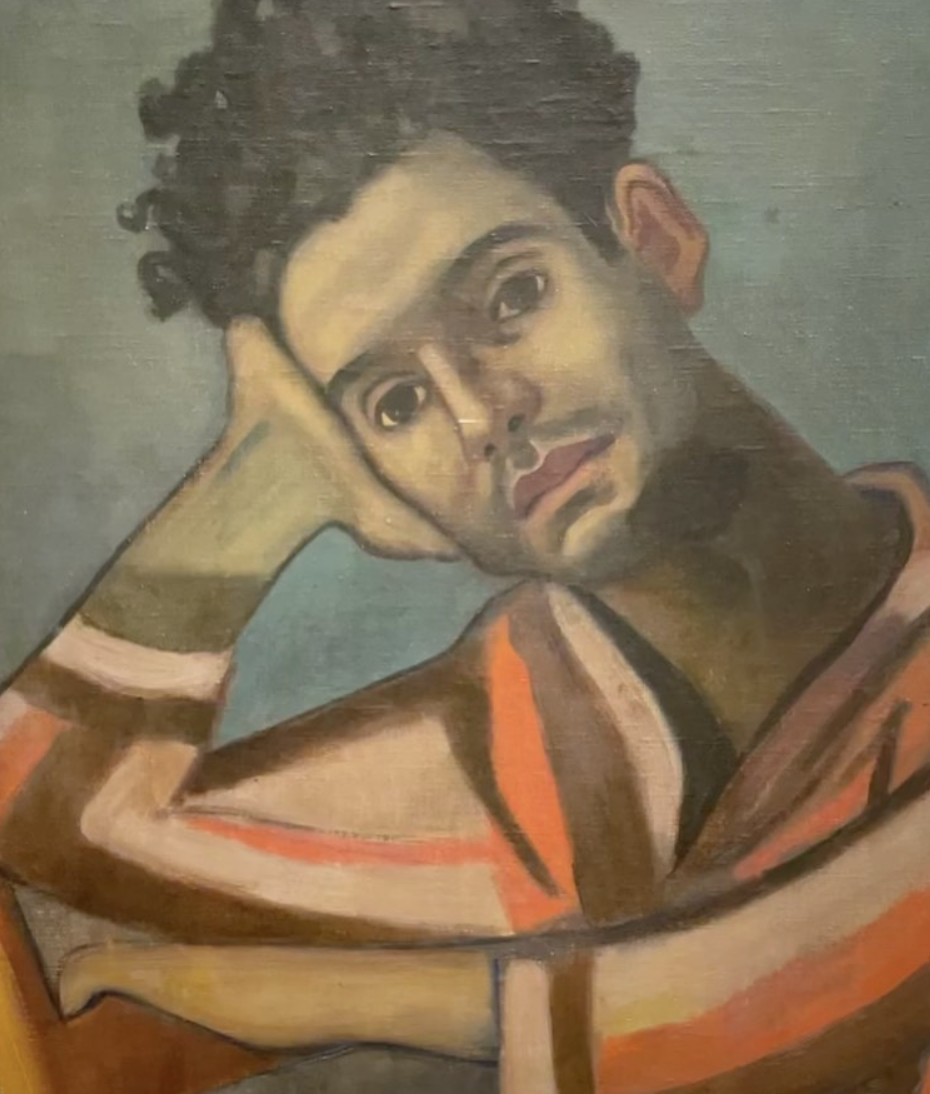

Though we are often warned not to conflate the life and the work, with Neel, it's impossible not to be struck by the number of marriages she tore apart, and the number of relationships of her own that seemed fungible. Neel felt free to pursue her passions, be they artistic or romantic. Some blew up on her. Her relationship with Carlos Enriquez ended in abandonment along with the death of one daughter and the hijacking of another and her subsequent hospitalization for a nervous breakdown. Hot tempered seaman Kenneth Doolittle burned and destroyed a large archive of her art. John Rothschild left his wife for her, but she did not commit to him. Perhaps he reminded her too much of her more conventional Pennsylvania background. Jose Negron, a salsa band leader, pictured here in 1936, left his wife for Neel but interestingly, she ended up using her as a subject.

Not long after they got together, they moved to Spanish Harlem and she began the prolific, clear eyed rendering of her friends and neighbors that is such an important part of the exhibition. They had a child, Richard, together (originally called Neel!) but Negron moved on a few years later to another woman.

The libertinage of the age went along with the politics, and the artistic milieu. Inevitably, there was collateral damage. But at the Met, we see the affection she once bore for her lovers in her indelible portraits. West coasters take heart: the show comes to the deYoung in 2022.

Jose1936, Estate of Alice Neel

Dana Schutz's First Show at Zwirner

There is nothing I anticipate more in contemporary art than seeing a new drop of work by artist Dana Schutz. I have followed her career and written about her. But nothing replaces the explosion of delight, intrigue and emotion that seeing the works in person evokes. This painting is so complex and filled with allusions and references that it is something worth studying up close. Alas I could not extend my stay in NY to see the new works at Frieze New York, but I am happy to be able to share this one with you and get your reactions. Entitled The Arts and rife with collectors with pearls and baseball bats scrambling over each other to get at the works of art, critics, dealers ( this is Dana’s first show with her new mega gallery Zwirner) and a general melee, perhaps this is Dana’s wry take on what the scene at the first art fair to emerge during Covid will be.

Dana Schutz, The Arts, 2021 © Dana Schutz. Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner.

Deluge IIs Painting Holds Truth Today

In all the turmoil about Philip Guston’s Klan paintings and the radical decision to postpone his retrospective I had forgotten this marvelous painting at MoMA which stands out there even among all the other standouts and classics. Deluge II painted it in 1975 at another point of inflection in the world (war /AIDS/drugs et al) felt so spot on for today’s pandemic deluge with its disembodied, muted heads, floating shoe and leg debris, and violent reddish hues. It reminded me of another famous painting which once hung at MoMA in the 70’s which also bespoke the horrors of war but in the end represented a wholly uncontrollable force visited upon an unsuspecting population, Picasso’s cry of rage and pain, Guernica.

Salon 94 Shows Early Saint Phalle

I made it to the stunning new gallery space for Salon 94 just as the Niki de Saint Phalle pieces were being prepared for their crates. What a joyful and rich display of this talented artist’s work. It felt like the gallery had met the moment joining these pieces in a long overdue tribute which showed the enormous energy and serious craftsmanship that even her mini Nanas demanded. Saint Phalle launched her own production line to fund her art- dreading ceding power to any funders or committees. While she was reviled for this in her lifetime, considered too crass and commercial, she took control of her output as a way to make more art. And they look spritely and gay and much like Calder’s circus, they were a path to other opportunities.

Lygia Pape Finds Inspiration in Brazil

I thought this image from the upcoming Lygia Pape show at Hauser & Wirth LA opening this weekend was apt for Earth Day.

Like Brazilian architect Lina Bo Bardi, more or less her contemporary, Lygia Pape found in the indigenous populations of Brazil a new way of aligning her practice. Though a member of the Concrete and then Neo Concrete movements in Brazil which favored the primacy of the viewer and interaction with a work of art, there is some Surrealism and even Pop in Pape's work. The body and its intersection with geometry is apparent in her later, more three dimensional work.

The Tumpinamba tribe which used red feathers in tribal ceremonies, apparently devoured their captives not for sustenance but to absorb the spiritual capacities of the "other". Pape seems to have absorbed other cultures in the same way, digesting them to see how others interpreted the world.

This red-feathered ball with the hand reaching out from inside, reminded me somehow of the old Negro Spiritual, "He's got the whole world in his hands." Only this time, SHES got the whole world in her hands. I look forward to seeing the show.

Memoria Tupinamba 2000 courtesy Projeto Lydia Pape and Hauser & Wirth

Christo levitates

Not long after his friend Germano Celant’s death Christo now follows. Christo taught us how to see things with fresh eyes, to notice things we may have passed many times by adding something that transported it to another realm. A lake is not just a lake (Iseo, Italy) a fence not just a fence (Running Fence, California) a bridge not just a bridge (Pont Neuf, Paris) a path not just a path (The Gates, Central Park) a building not just a building (Reichstag, Berlin) and so on. He was about to teach us a monumental arch was not just an arch (Paris Arc de Triomphe). Here at Lake Iseo in 2016 he taught us how to Walk on Water. His nimble, creative audacious eye and spirit will be missed.

The mysteries behind Man Ray's Les Mysteres Du Chateau de De

In 1929 artist, photographer,filmmaker extraordinaire Man Ray was invited by one of his ardent patrons, the Vicomte de Noailles, and his infamous wife and partner in outlandishness, Marie-Laure, to their Robert Mallet-Stevens designed chateau in Hyeres, in the South of France, to shoot the house and its varying, dynamic collections as well as “make some of shots of his guests disporting themselves in the gymnasium and swimming pool,” according to Man Ray. As with many Surrealists who favored automatic writing, Man Ray favored a kind of automatic filmmaking. He looked upon film as another tool in his poetic, playful bag of tricks innovated with light but he had grown disenchanted as reality in the form of sound had begun to impose itself on the medium: improvisation was his preferred metier. Nevertheless, the Vicomte assured the artist that the film would be a documentary for their private viewing pleasure only, so Man Ray made an exception for the wealthy and generous man. Reminded of a Mallarme poem, “A throw of the Dice can Never do Away with Chance”, Man Ray decided to make, ‘chance’ the theme of the film. He brought with him two pairs of dice and six pairs of silk stockings which he intended to “pull over the heads of any persons that appeared in the film to help create mystery and anonymity.” Things being what they were at the Chateau, that is to say, already capricious with the beau mode in attendance, the film did not follow a neatly proscribed narrative.

Man Ray began shooting when he left Paris. Two men throw the dice, and leave for the south, arriving at the angular chateau—which is as much a character as anyone in the film. A couple throws the dice and decides to stay, then just as enigmatically to leave after another toss. Man Ray captured the right angles of the Mallet-Stevens modernist house, the painting archives, and eventually the frolicking guests shrouded in stockings and striped bathing suits as if in a phantasm. (Indoor gyms and exercise were all the rage in the late twenties; somehow the late nights and flamboyance had found a counterweight). The Vicomtesse appears in an underwater sequence with oranges in the glass-covered pool, a surreal Esther Williams; a stocking almost actually choked the Vicomte.

Les Mysteres du Chateau de De film also contains negative images akin to his signature Rayographs. This film was his last complete film. (By way of reference, the same year, Bunuel’s Un Chien Andalou was released).

The Gagosian Gallery in San Francisco has a very engaging show with good quality prints of Les Mysteres and two other films and numerous objets and stills drawn from the films as well as a short history of the house, now the Villa Noailles, an artists retreat. In a time when most films are literal-minded, these instead make the viewer a participant who is obliged to connect the dots—and the dice.

MAN RAY

Film Still from Le mystère du Château du Dé, 1929

Gelatin silver print

11 13/16 x 14 9/16 inches

30 x 37 cm

© May Ray Trust/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris 2019

Image courtesy Gagosian Gallery

Anni Albers: A Visionary

Anni Albers was first known as her husband Joseph’s wife. The Bauhaus was purportedly egalitarian however and though textiles largely a female ghetto, the many exhibitions of her innovative work since then prove her intrinsic worth as a designer. A new exhibition at David Zwirner gallery tells the tale. Photo courtesy of David Zwirner Gallery.

Kader Attia at Berkeley

Kader Attia’s work asks: How do individuals and social bodies enact a process of healing after having suffered both physically and psychologically during major political conflicts? A new exhibition at Berkeley Arts Studio explores the French Algerian artist’s work.

William McCance, an anti war activist Scottish painter

After being imprisoned for conscientious objection during WW1, William McCance still refused to conform. McCance rejected the more conventional art which flourished in Scotland in the 1920’s like Cecile Walton. Instead, influenced by the Cubist elements wafting over the Channel, he began a series of paintings which reflected his anti-war stance. This painting at the Kelvingrove Gallery, Glasgow, from 1922 called ‘Conflict’ offers aggressive shapes which appear to be almost Guernica-derived. An outlier in the largely Art Deco decorative environment, he turned to book design and teaching in London and Wales. He had a small touring retrospective in the UK in the 70s but has largely been lost to history.

The Ladies Waldegrave

Uncle Horace (Walpole) commissioned Joshua Reynolds to paint his nieces, the ladies Waldegrave, in 1780. Though they look to be purely Three Gracelike in their white dresses, making lace and spinning silk, the portrait was actually a come-hither to potential suitors for Charlotte, Elizabeth and Anna who were still single. It was the 18th century version of Tinder.

An unusual and poignant image of Frida in pain comes to auction

Frida Kahlo underwent something like 40 surgeries to correct the cascade of physical ailments (possible spina bifida, polio, a horrendous bus collision which had driven an iron handrail into her pelvis) which tormented her but which gave her paintings, often made from her convalescent beds, a very particular vantage point and haunting quality. (Kahlo also worked with mirrors to serve as the limbs she was not able to mobilize). This photograph, which I’d not seen before, was sold at Sotheby's—as part of a Nickolas Muray collection— for 28,000 dollars.

Muray is the Hungarian born US based photographer with whom she had a decade long affair. He was married four times, Kahlo almost as many (counting the re-marriage to Diego Rivera, whom she considered her true soul mate.) but they stayed close. Frida in Traction, was taken in 1940 when Muray visited her in the hospital in Mexico, and goes tight on Kahlo’s face which allows the uncertainty of her gaze—will this surgery be the answer?—full measure. Is she accepting or fearful? The folded white cloth around her famous unibrow signifies a moment when Kahlo was incapable of facing down her legacy of pain through her art. But works made that same year which include necklaces which cut into her neck and make her bleed and hearts which are ex-corpus, show she was the eternal phoenix. Muray once wrote to her that he wished he could find “the secret how to make you well again so you could sing, and smile, love and play again as I have seen you before in the bright sun or in the dark night.” As a document of one of those times when she was not able to vanquish her pain, it is unforgettable.

Photo by Nickolas Muray; © Nickolas Muray Photo Archives

The Brant Foundation reminds when art was the thing

In the midst of all the brouhaha about architecture gone wrong from coast (Hudson Yards) to coast (Lacma), the new Richard Gluckman building for the Brant Foundation in New York stands as a model of discretion and an excellent showcase for art. Remember when the art was the thing? The ceiling pool that greets you in the brick walled space feels like a dreamy light filled upside-down Turrell rather than a gimmick, you’re underwater without having to hold your breath. Gluckman has taken many inspirations from the mid century (Quincy Jones?)—the mullioned windows, the white birch landscape, the decomposed granite hardscape—and the wood plank or brutalist ceilings (Mendes da Rocha?) and supersized them made them neater and grander, but still, dare I use this word, tasteful. The view from the top 4th floor in particular is neatly centered on a church spire and the Manhattan one sees is not the new pencil thin spires dotting the island but rather the humbler East Village of yore. The Basquiats are plentiful and look very well in the space, especially enchanting when hung salon style downstairs, and a friend and I calculated that he was only in his early twenties when many of them were painted. They feel electric —a young black prodigy whose time was over too fast communing with Walter de Maria who had repurposed a ConEd station for his studio. Basquiat’s capabilities as a wordsmith—he almost seems to playing a version of Jotto with himself—also come to the fore. It was a pleasure to like something so unreservedly for a change.

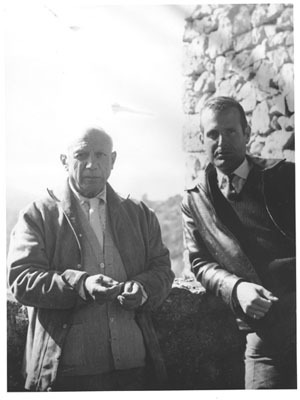

John Richardson dies at 95, a biographer of Picasso equal to his lifelong subject

The following is an excerpt from my Huffington Post piece on Volume III of Richardson’s Picasso biography.

…All the more reason then to be worshipful and impressed at the astounding work of John Richardson who has produced the third volume of his biography of Picasso, The Triumphant Years, published this week to great acclaim. Richardson’s unflagging erudition, meticulous reporting, insatiable digging, clever connections, and vast and deep personal knowledge of the players makes this series much closer to a performance piece of biography , the definitive text.

And because Richardson makes it perfectly clear with engaging narrative and precise scholarship how worthy his subject is, even those who have read about Picasso before will be newly swept away by the intricacies of this complex character. This is not, however, just a tome for insiders, though it helps to have a healthy interest in art and artists.

Richardson met Picasso while living with Douglas Cooper (who had himself wanted to write the biography) in the south of France and saw him regularly from the early fifties through the early sixties. He began by thinking he would write about the wives and mistresses of Picasso, the way the artist used art and sex, painting and making love, as metaphors for each other and how the style of his work changed as he changed women—volatile relationships that Dora Maar, herself one of the mistresses, characterized to him as ‘first, the plinth, then the doormat”. This was the template we used on the film, (WNET, Picasso, A Painter’s Diary) and it’s reductive and catchy, certainly one way to process the gargantuan archive when you only have ninety minutes.

But as Richardson himself says, “Picasso’s work is far too protean and paradoxical to be limited to a single reading.” And so he abandoned that seductive narrowcasting at the outset in favor of a much more comprehensive and penetrating approach.

One that would more or less take the rest of his life.

Richardson isn’t the first to devote most of his life to Pablo, as the volumes make clear. The Picasso bibliography includes everything from kiss and tells to scholarly treatises about the work and any number of memoirs and biographies. (Richardson is impatient and dismissive of some of these earlier efforts, calling them everything from “unreliable” to “rigamarole” or “fairy tale” to outright “wretched” or “sheer fantasy”.) But his end result is entirely different. Encyclopedic without being boring, any future artist’s biography, or really any biography, will inevitably have to step over Richardson’s very high bar.

Occasionally, biographers manage to be fans of their subjects for the duration. It’s hard to love someone unreservedly whom you come to know so intimately— Richardson doesn’t shy away from scandal, rather he is propelled by it, and sometimes, if this works to Picasso’s disadvantage, so be it. Looking at a life from the perspective of the warts and all can produce battle fatigue but at the end of the third volume (the ballets, the project for a memorial to Apollinaire, the bourgeoise life with Olga, the flirtation with Sara and Gerald Murphy, the rebellious hedonism of his attraction to the seventeen year old Marie Therese) with Picasso shrugging off Surrealism and heading for the shattering Guernica, one still feels Richardson’s magnificent enthusiasms for the moods, the settings, the entourages that may have influenced him; the motivations, the myth-busting, the sexual/historical/empirical digressions often taking us far afield only to bring us back a bit later with a much richer understanding of what made this man, and his world, tick.

The volumes look and are dense, (Volume 1 ranges from 1881-1906, Volume 2 from 1907- 1916 and Volume 3 from 1917-1932) but they are intensely readable—chatty, personal, with mini- biographies of others in the Picasso circle—so that we come to know just how convoluted and complex the roots of the art were with Pablo often devouring the hands that were feeding him. The tangents, however “vaut le detour” and are every bit as juicy as the three star view of the man himself. Often, Richardson makes patently clear, Picasso was conceptually leagues ahead of everyone else. But at times he was in debt to other geniuses who were his friends and competitors-Braque, Gaugin, Matisse, Seurat—and to the other protean talents from whom he freely stole(Manet, Ingres) ideas and images.

The normally heavy lifting of biography thus seems like gossamer in his hands, the facts arranged in such a way as to ease you on down the road with the tone of a confidence or a wink. The iconography of each important work is disarmingly traced, threading the personal and professional antecedents into one comprehensive whole. There are no sacred cows for Richardson—and like a cat he sneaks up and circles the truth and then pounces on it, explaining the artistic breakthroughs, the changes from one style to another, the sexuality and drugs which fueled some of them, and Picasso’s own drama-king ego that self-mythologized to the point that he came to believe in the stories too. As a myth debunker Richardson, however, is unsurpassed, adroit at peeling the layers: first, those of Picasso himself, then the second generation contemporary witnesses who often rewrote history, then the third generation anecdotal whispers, the fourth generation scholarly reckoning, and so on, often a daisy chain of prior confabulation.

Richardson leaves no dwelling, no voyage, no influence (the wonders he saw and appropriated into his own work), no woman, no friend , or enemy uncharted. One resists the tendency to makes lists only with difficulty: the houses (in Volume Three alone: Montrouge, rue la Boetie, le Gueridon, La Vigie, la belle Rose, la Haie Blance, Boisgeloup), the Women (madcap Fernande, lissome Eva, bourgeoise Olga, , sexpot Marie Therese, free spirited Francoise, imposing Jacqueline), the friends (Apollinaire, Cocteau, Jacob, Breton, Gertrude Stein, Stravinsky, Diaghilev) and the enemies and some that straddled the two camps, the Dealers (Kahnweiler, Rosenberg), the ballets (Parade, Tricorne, Pulcinella, Mercure, L’epoque des Duchesses, La Danse), the Museums, (besides Paris, Antibes, Barcelona and now Malaga) the Galleries, the retrospectives and exhibitions, the media (paint, sculpture, photography, poetry, collage, tapestry). All come under his watchful, painstaking and often bemused eye.

Richardson’s gift for language also has the added bonus of a mini-tutorial in French and Spanish slang —gratin (high society), bien couillarde (ballsy, or well hung), tertulia (group of friends).

And as far as wrangling goes, Richardson is unrivaled. Some of the images were a revelation to me; many classified or in private collections that were being carefully concealed at the time of the documentary but his long personal cultivation of so many of the Picasso personages has reaped its rewards and the astonishing selection of photographs from the Olga years in Volume Three is testament to this.

Richardson notes that for most of his life, Picasso was already in the spotlight, that the tributes and retrospectives one normally gets at the end had been ongoing since his twenties. Little details, why Picasso’s black was blacker than black (he added silver powder) or his relationship with Chanel (one night stands) make the reading lively. But it also helps to be reminded of his early genius, the sheer power of his intellectual and instinctive audacity—the breakthrough Demoiselles D’Avignon for example,was painted when he was 25!

In short, Richardson seems to have found a way to see Picasso plain while at the same time respecting his obviously century-dominating genius. Fernande, an early “official” mistress apparently said, “He who neglects me, loses me” and Picasso might well have intimated the same thing. Fear not, Richardson has made amply sure we won’t.

Dorothea Tanning opens eyes and doors at the Tate Modern

Like Warhol, Dorothea Tanning, the subject of a new retrospective at the Tate, toiled first in advertising when she came to New York. She had been deeply affected by the groundbreaking MoMA Surrealism/Dada show of 1936 and her ads for Macy’s and others reflected this new awareness of the ability to disassociate body parts and imagery.

She herself was selected by her future husband Max Ernst—then married to Peggy Guggenheim—for a show of women artists at Guggenheim’s Art of this Century gallery when she returned from a stay in Europe. (Was this the moment of the Ernst-Tanning coup de foudre? A year later they were together) Georgia O’Keefe refused to be relegated to this show of ‘women artists” but Tanning accepted. When next invited to participate however in a women-only show in the 70’s second wave of feminism, like many creative women who had already made their own way (Mary McCarthy, Lillian Hellman et al) Tanning was also finally a refusnik. ‘Women artists,” she said, “There is no such thing – or person. It’s just as much a contradiction in terms as “man artist” or “elephant artist”. You may be a woman and you may be an artist; but the one is a given and the other is you.’

She had by then grown into a bold, incisive, self-confident practitioner of painting, poetry, sculpture, costumes and set design.

"Just put yourself in my place, George, " she wrote after she had, in a labor of love, produced the costumes and sets for Balanchine’s new ballet Night Shadow, supported by Lincoln Kirstein, "and you would cry too." Tanning was passionate about ballet, but her production had an unfortunately short shelf life when a new production by the Monte Carlo ballet appeared just a few years later. "I really thought all this time that I had helped to make it a good work, and lots of other people thought so too. I was proud to have worked with you to make such a pretty ballet and I felt it was a real collaboration of all 3 of us. But I suppose it’s a very complicated story and I don’t understand very well how these things work."

Tanning went on to work on other ballets and had plans for many more, but was thwarted by lack of funding and the nature of the collaborative process which stymied her as a solo practitioner .

I wonder what Tanning would have made of the many women-only international shows organized this year in response to #MeToo. Ghetto or Gift? The concurrent counter narrative solo exhibitions—besides Tanning (Ernst), Lee Miller(Man Ray) and Gala Eluard (Dali)—who have finally been removed from the rolls of the ‘muses’-only, tell a more complete tale.

The exhibition runs from February 27 to June 9, 2019 at the Tate Modern. All images courtesy of the Tate.

Dana Schutz at Petzel Gallery: Imagine Me and You

Dana Schutz’s new show at Petzel opens on a woman painting in an earthquake. Her sneakered foot rests on a skull.

I think of Schutz having to work after the earthquake of the last Whitney Biennial, debris flying at her that she never expected, yet managing in spite of the --in my opinion--wholly undeserved misplaced vitriol about her painting of Emmett Till, to carry on with her work and her life.

Another painting in this collection shows a woman on a treadmill watching a blank screen. Maybe this was the only way to exorcise that troubling time.

We are told as readers never to conflate the work with the writer. And yet it’s impossible not to conjure up the life surrounding this new work, at odds with a self-effacing, private self. Instead it is filled with monsters and demons, bold slashes of color, trouble, wandering, marching and strangers as well as the occasional more pastoral: the sun, a boatman, a mountain group.

My favorite image, having spent the previous evening with Manet’s Odalisque is Schutz’s equally provocative version, a green eyed woman who boldly confronts the viewer, refusing to sink beneath the waves, a pelican with a raspberry standing in for Laure and her bouquet of flowers.

Shutz imparts more emotion into a finger or a limb than most artists can into a face. Each element of a body is articulated. It reminds me of flamenco dancing—sometimes your head is going one way, your hands another, your body yet another. Your feet are stamping to get attention. Yet somehow the whole makes sense if you add enough emotion. Emotion is the overlay to Schutz’s more formally excellent qualities. I feel a gut punch at every image.

There is still plenty of Philip Guston in Schutz and even Picasso, but that’s all to the good. Schutz is not afraid to reference her heroes and heroines, to give credit where it’s due. Her bronze sculpture is new and engaging, her painting impasto translating readily into the dynamic, often humorous creatures as if Giacometti had run riot.

I am obviously a fan of Schutz’s bold and ambitious work. I believe she is one of our leading, most authentic artists.

Dana Schutz, Imagine Me and You, Petzel Gallery, 18th Street, open until February 23.

Posing Modernity at Columbia University's new Wallach Gallery

Posing Modernity: The Black Model from Manet to Matisse to Today has a long title but in this case its thoroughness mirrors the truly deep and expansive exhibition at the Wallach Art Gallery at the newish Renzo Piano designed Lenfest Center at Columbia University. Based on her disseration, Denise Murrell has curated an investigation of gender, race and class via the role of black female model in 19-21st century art history.

It’s the precisely right exhibition at the right time at the right place.

Sponsored by the Ford Foundation, the exhibition takes as its premise the centrality of the black female figure in modern art, that these models were both much more important to the development of painting and to the personal lives of their painters than anyone has presumed. No longer exotic, they were full participants in the culture. They became individuals instead of stereotypes.

There are so many surprises in the exhibition that my companion and I, an erudite former curator and head of a foundation found ourselves constantly stopping and pointing things out to each other.

Who knew that Alexandre Dumas pere was black?

Who knew that Matisse regularly visited Harlem?

Who knew that La Dame aux Camelias and subsequent adaptation La Traviata was based on the story of a mixed race American actress called Adah Mencken who had been one of Dumas’s many mistresses?

Who knew it was Baudelaire’s visits with actress Jeanne Duval and his sessions with Laure, both Civil War era free black Parisians that inspired Manet’s Olympia and other paintings?

Olympia is alas not here but you can always find her luscious white body, her black cat and Laure as her maid carrying flowers at the Musee d’Orsay where this exhibition is next destined. We are sorry to miss her in the flesh, since so much of the exhibition derives from this historic painting but instead we have a variety of prostitutes, nannies, slaves from the West Indies, circus stars and grisettes from Paris in images from Nadar, Degas, Norman Lewis, James Porter, James van Der Zee among others. it is another kind of bouquet.

The show summons how extensive the pattern of black modeling was for 160 years, how close some of the models were to these famous painters, and how much their work was influenced by the then novel inclusion of their race and gender in works no longer destined for the salon. The legacy of Olympia runs deep and long. The last room is devoted to contemporary riffs on the Manet from Ellen Gallagher to Mickalene Thomas.

For me, even as a writer not a painter, the painting has cast a long shadow, summoning the 19th century literary heroines who were both revered and sometimes destroyed by their desire and devil-may-care. Behind these paintings were some very brutal stories of painterly and writerly disaffection and dismissal. Yet in the end, these models have more than withstood the test of time and represent an uplift of subject and grace.

Columbia’s new complex of buildings by Piano is a fine home for the show and rightly sited in Harlem and it bodes well for the university as a legitimate and first tier venue for class A material. Congratulations to all.

Baudelaire

Manet

P S. I include two images of Manet and Baudelaire not only to show you how lively and modern they look but also to see that it’s possible that Baudelaire was separated from Bill Murray at birth!

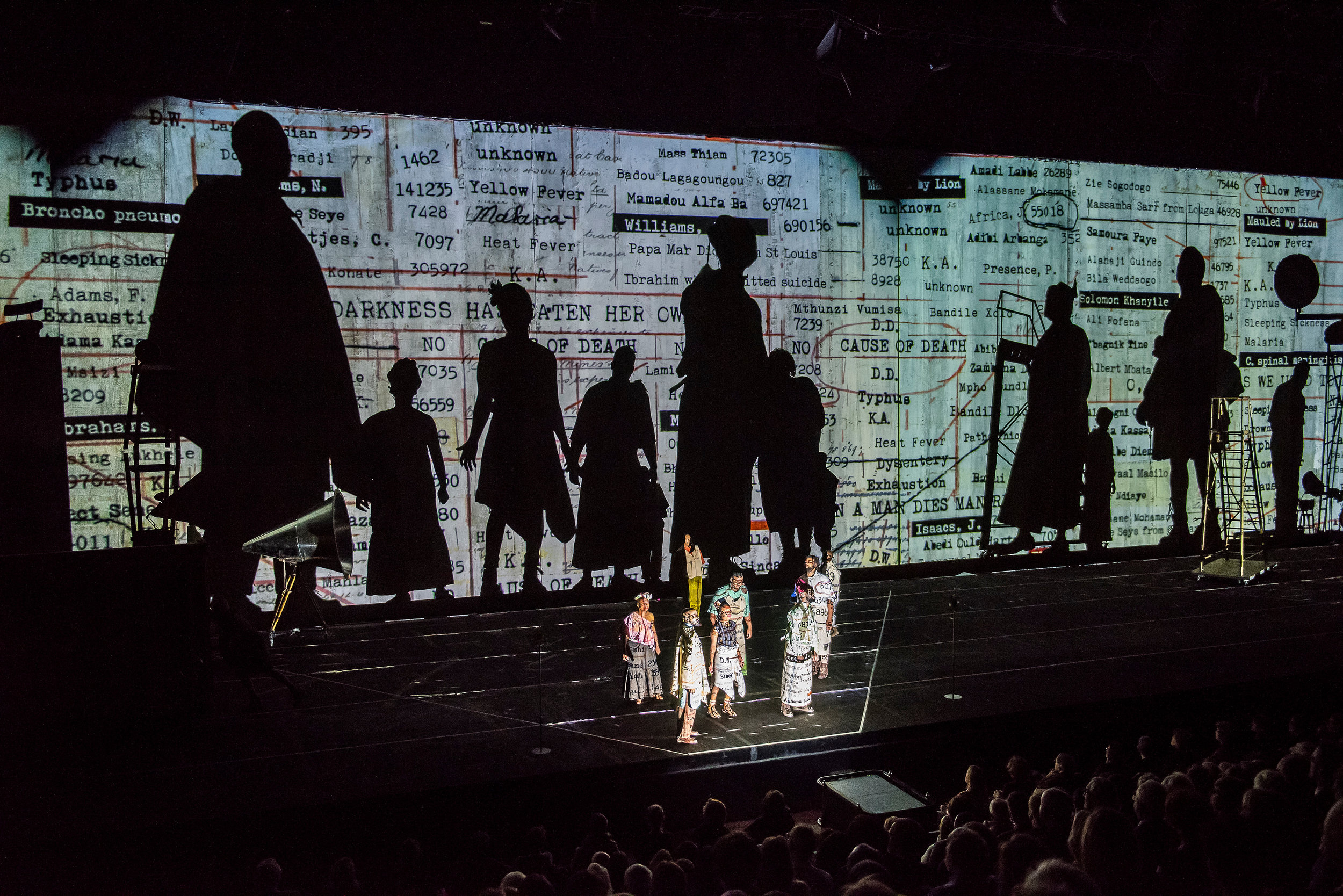

The Head and the Load: William Kentridge pulls focus on Africa and WW I

William Kentridge is a polymath, an entrepreneur, a ringmaster, an historian, a singer, a writer, a visual artist, a designer, and so on. There is probably no challenge too great for this maestro of the visual and performing arts.

The Head and the Load, a production workshopped at his The Center for the Less Good Idea atelier in Johannesburg and at Mass MoCA, and performed already at the Tate and in Germany, arrives at the Drill Hall of the Park Avenue Armory already finely tuned. I’ve long had trouble with seeing productions try to successfully fill this vast space. But apparently if you build it they will come—and there is no one better than Kentridge to think big.

Taking as his ostensible subject the role of Africans in WW 1, Kentridge envisions a world where Africans are finally allowed to speak truth to power about what it was like to be a human vehicle (soldiers and porters) for troop strength and munitions during this global war in which Africa became part of the spoils. With his principal collaborators, composers Philip Miller and Thuthuka Sibisi, choreographer Gregory Maqoma, a local NY chamber orchestra The Knights and other accomplished dancers, singers, musicians and actors, Kentridge deploys some of his signature elements: live and video shadowplay, original documentation, animation, processionals et al) and delivers a vast and moving panoply of heartbreak and political strife.

In an artists talk before the performance, Kentridge described the gestation of the piece in an 8 day workshop in Joburg with 60 artists that gradually evolved over the course of other subsequent workshops. Some elements were also stimulated by his processional piece in Rome on the Tiber River. For The Head and the Load, Kentridge modified this processional approach with waystations: breaks for us to understand the deeper history and meanings of the conscription of native African troops into a far away war they barely understood.

English, French, German and African languages are deployed alongside voices in an arsenal of sounds that both emulate aspects of the destruction and elevate it. Having seen Kentridge perform the Schwitters Ursonate last year I heard the elements of Rakka Ta Bee Bee in the opening moments. Instruments are voices, voices are instruments, and as Kentridge says, he would be hard pressed to find opera singers who would challenge their vocal equipment quite so audaciously as these performers are willing to do.

Kentridge is recalling Dada and its emphasis on collage, on the spoken automatic word, on repetition as a tool for engagement. But the most affecting moment for me was the extraordinary pas de deux between two soldiers, one in a state of collapse, the other trying to haul him up and get him to salute. This is probably the most affecting new piece of choreography I have seen in a very long time, and is as moving and intricately plotted as any of the Swan Queen with her Prince. Kentridge says he wanted to emphasize the contrasting “tenderness and violence”

Kentridge resisted the temptation to focus on one character’s three act journey, a more conventional operatic approach. Instead this collage method (his default) allows him to graze on many stories which percolate, evaporate and then re-constitute as the evening progresses.

I still have trouble with the Drill Hall. My head moves in a kind of robotic 180 degree rotation, trying to capture the fullness of what the team is showing me. It’s not only tiring, I think it distracts from the pithiness, the anguish, the intensity.

But ok. Here’s a guy for whom the work size is irrelevant. He can work small (Ursonate) or large (The Nose), in museums, or in performing arts venues with equal aplomb. He is bravely opening a different window on non-western culture and history for all of us and is to be commended.

The Head and the Load continues at the Park Avenue Armory through December 15.

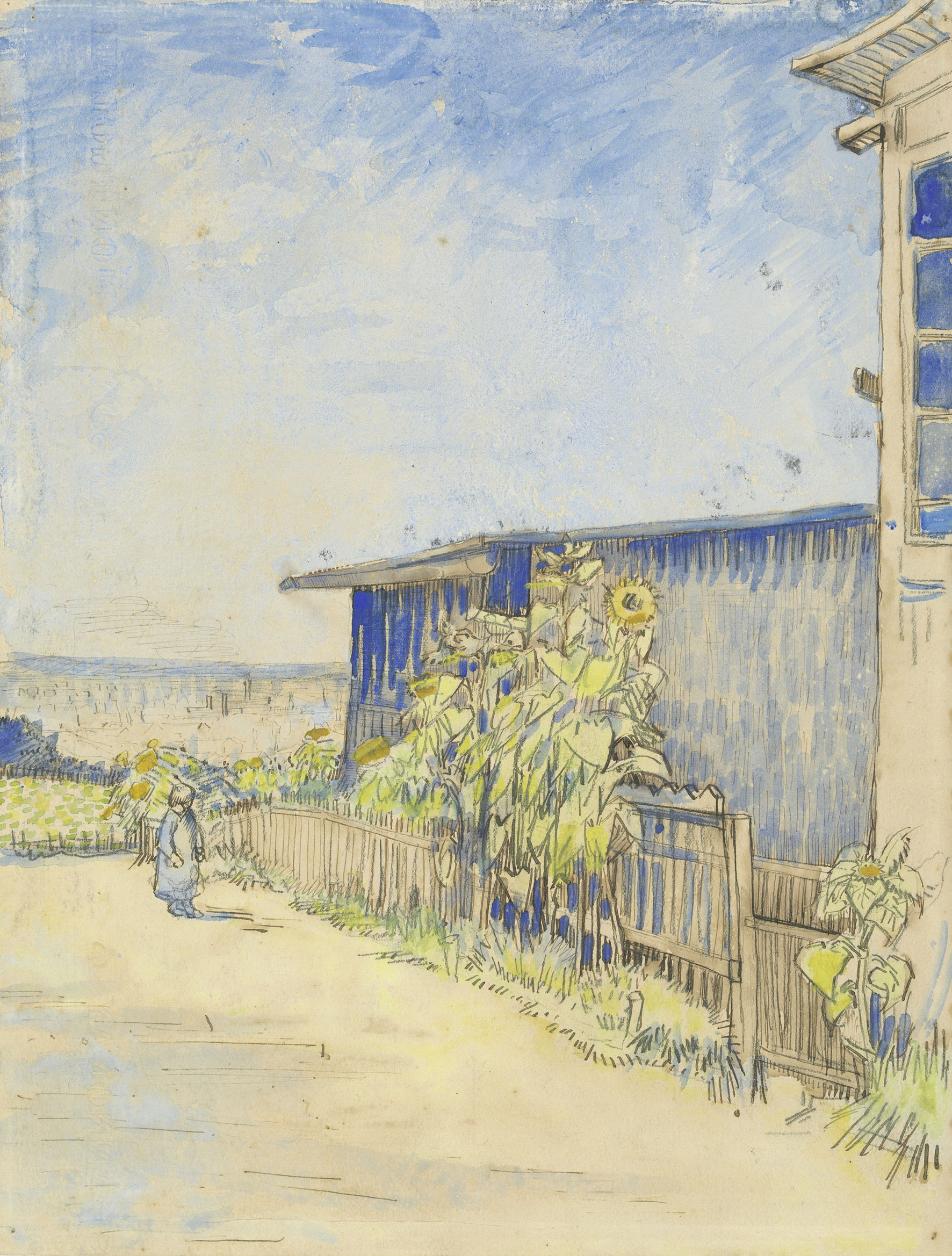

Van Gogh by Julian Schnabel: At Eternity's Gate

Julian Schnabel is a very brave artist. After being a wildly successful artist du jour and then coming down off that perch, he turned his hand to film and made, among others, some beauties: the story of Basquiat and The Diving Bell and the Butterfly.

At Eternity’s Gate, his film portrait of Van Gogh is as ambitious as the others but is hampered more than anything by the dialog seemingly lifted in whole chunks from letters that Van Gogh wrote to his brother Theo, to Paul Gauguin fellow artist, and others. Despite help from veteran screenwriter Jean Claude Carriere (or maybe alas because of it) nothing ever sounds natural. And therefore the performances, though earnest and deep, draw attention to their static quality instead of to their verisimilitude. Schnabel should have trusted himself more.

Instead of bringing on a French screenwriter, the casting could have been more European. Not that I am PC about that. But the American-ness and British-ness of the principal roles doesn’t help you dive into the characters.

Willem Dafoe is abjectly tortured, (even if a good thirty years older than the artist actually was as this series of events unfolds), the artist who can’t get anyone to even hang his work for free in a bar, whose manic depression overwhelms him, whose obsessions for capturing on canvas a girl walking home from work or a fellow asylum mate get him into trouble. His compulsive desire to fill every canvas, to layer it, to exhaust the paint itself, is made real and here Schnabel’s own expertise comes into play. We feel keenly his desire to suck up the sights, sounds and even smells of the world.

Oscar Isaac is a suitably arrogant Gauguin who alternately thrills and chills his less successful friend. The best surprise is Rupert Friend as brother Theo.

This relationship of the brothers is wonderfully drawn: Theo the sane, Vincent the genius madman, linked forever as helper and helpless. Theo’s desire for his own life eventually overrides his compassion for Vincent when he institutionalizes him.

Van Gogh’s intellectual heft, his knowledge of Shakespeare and the Bible is set against his dramatic deficits of personal intelligence. I don’t know if Schnabel invented this or it was real. (I reached out to John Walsh, ex Getty director, now giving a series of lectures on Van Gogh at Yale open to the public for some context. Walsh reminded me he would be dealing with this period in Arles next semester .)

The production is filled with the southern French light that so warmed Van Gogh’s aching heart and soul. (Arles, once a favorite city of mine, is now undergoing massive development by the Luma Foundation. I saw things in construction a few years ago. I’m hopeful they can retain something of the city’s historic character) Schnabel managed to find the still rural Arles, the one that was Van Gogh’s home at the end of his life both inside outside the asylum walls.

Every loaf of bread, bowl of fruit and indeed every character from barmaid to priest is filled with the unique texture of real life. And then every once in a while the screen goes black. A moment of darkness descends on us just as it does on Vincent.

The film opens on November 16th.